July 11, 2022

Last week I provided a summary of the CRTC’s tectonic shift in regulating audio visual broadcasting. The occasion was its renewal of CBC/Radio Canada’s television licence.

The three-to-two majority ruling endorsed by Chair Ian Scott made three dramatic licence changes.

Its headline move was to guarantee programming dollars for Indigenous and equity-seeking communities (racialized, disabled, LBGTQ and official minority language communities). That spending envelope will be 35% of CBC’s programming acquisitions on the English network and 15% on the French network.

This should deservedly earn the CRTC praise. But it was two other regulatory changes that were unexpected and resulted in strident dissents from two prominent Commissioners, Broadcasting Vice Chair Caroline Simard and Ontario Commissioner Monique Lafontaine.

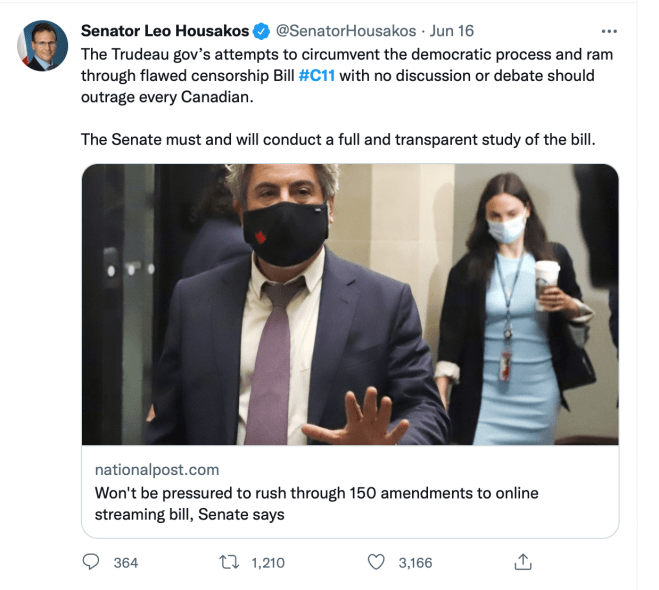

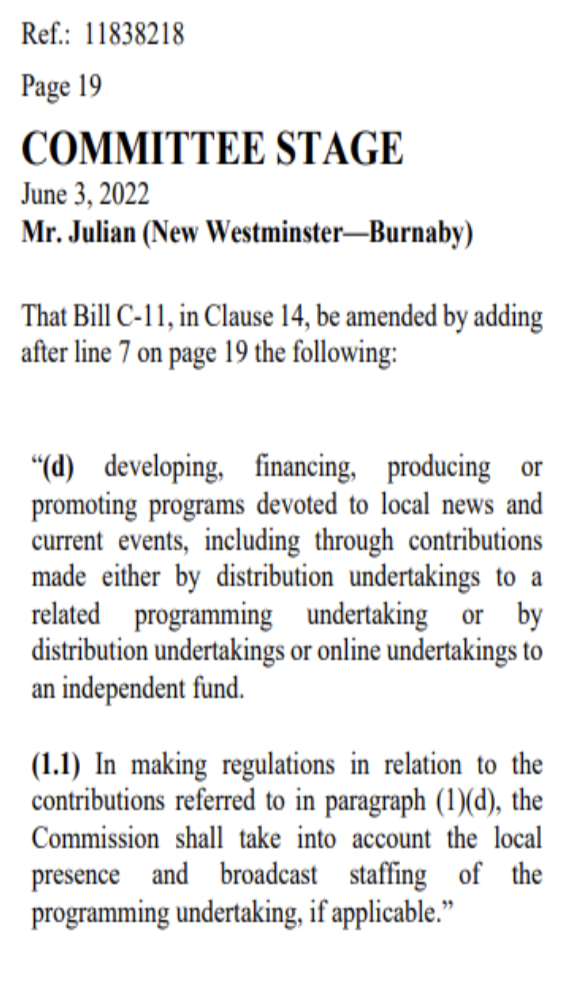

The first change was to merge the CBC’s existing Canadian programming expenditure obligations for its core television operation with its digital platforms, until now unregulated and without any conditions of license. Going forward, the CBC is free to shift an almost unlimited amount of its linear television budget to its digital platforms like CBC Gem, cbcnews.ca or their Radio-Canada counterparts.

The majority’s companion piece to this shared digital/linear approach to Canadian programming was to crop back the remaining conditions of licence on how much Canadian programming, especially local news, must be aired on the CBC’s network of 26 stations across the country.

Key changes were:

- Exhibition minimums for prime-time evening programming on linear television were eliminated;

- Exhibition minimums for “programs of national interest” (PNI) (i.e. Canadian stories in dramas and documentaries) were also eliminated, although they were replaced with conditions of license for continued spending that aligns with the CBC’s current budgeting.

- Exhibition minimums for French-language children’s programming were also removed on the grounds that Radio-Canada has far exceeded the 2013 minimums (English children’s programming has only just kept up, so the CBC keeps its license conditions).

- Most controversially, programming obligations for seven local stations in Vancouver, Calgary, Edmonton, Toronto, Ottawa and Montréal (French and English) were deleted and were not replaced by spending requirements or by any network-wide “news” spending obligation (the CBC’s English and French language national news services are regulated separately from its local network).

This is sharply different from the belt-and-suspenders regulations the Commission imposed in 2017 on private sector broadcasters who were not only obliged to keep their exhibition minimums for local stations but also to spend no less than 11% of network-wide revenue on local news.

The reasoning behind the majority decision seemed to be (a) accommodate a long-term shift of television programming to digital platforms and (b) trust the CBC will pursue the best programming priorities without having to strictly comply with standards of exhibition or expenditure.

Other than the easily obeyed obligation to spend 85% of its programming budget on Canadian programs on either digital or linear platforms, the remaining conditions of licence governing the CBC’s accountability are now mostly restricted to doing audience surveys, public consultations, and the reporting of data to the CRTC.

Dissenters Simard and Lafontaine zeroed in on the Commission’s unprecedented deference to broadcaster autonomy. According to Broadcasting Vice Chair Simard:

The majority decision proposes an approach that is different from the results-based approach applicable prior to the majority decision coming into force. The essence of this new approach consists in imposing conditions of licence requiring the CBC to file reports to demonstrate how its programming choices take into account public opinion research (or perception surveys) and public consultations. No binding measurable targets will be set by either the Commission or the CBC, either before or as part of this public opinion research and public consultation.

Lafontaine —the Ontario Commissioner representing nearly 40% of the national audience— agreed with that point:

Consultations and perception studies are not regulatory tools. CBC itself said that the perception studies, which it already conducts, are not appropriate tools for evaluating regulatory compliance.

Lafontaine also condemned the nearly unlimited pooling of the CBC’s Canadian programming obligations across linear and digital platforms:

In my view, the majority decision has approved a licensing framework for CBC/Radio-Canada that is fundamentally different from the Commission’s licensing approach for television broadcasting, without first conducting a detailed policy review to consider what, if any, measures would be appropriate for the digital age. We are therefore left with a majority-approved programming framework that allows hundreds of millions of dollars to leave the Corporation’s regulated platforms each year and flow to its unregulated online audiovisual platforms.

Lafontaine argued the majority was skipping over a vital policy discussion of how to regulate online platforms and was putting the policy cart before the horse for the entire broadcasting system.

It could hardly go unnoticed that this ruling for the CBC licence effectively sets a precedent for the upcoming renewal of licences for the major private broadcasters in 2024. Bell Media, Rogers, and Québecor compete with the CBC and will demand equal relief from regulatory obligations.

The implications of the majority ruling for local news is the most alarming. Their blasé repeal of all licence obligations to air programming at the seven local stations in our six largest cities came out of left field without any warning in the Commission’s 2019 Notice of Consultation that announced the public hearings.

After years of public concern over the decline in local news coverage —-which the Parliamentary Heritage Committee insisted in its 2017 report required dramatic legislative action—- the majority chose to repeal licence obligations for local news without identifying a compelling policy objective for doing so. They also declined to set news expenditure minimums for the overall network (as proposed by the CBC itself) which would have been a less drastic alternative.

Simard pointed out the obvious:

In the age of disinformation and misinformation, and considering the central and pivotal role that the CBC plays in providing reliable, unbiased and objective news, there is no legally binding framework in the majority decision in regard to news presented on the CBC’s digital platforms.

Lafontaine was concerned that CBC’s news spending may just migrate to its unregulated digital television and alphanumeric news websites:

With online news, who knows how the CBC will leverage its digital platforms, or other digital platforms, to innovate (one hopes) and, at the same time, rethink the exhibition of traditional television news reports….

…The removal of the minimum licensing obligations for local/news programming in metropolitan markets across Canada is inappropriate at this time given the crisis that has arisen in the provision of news and information. …

Canadians who reside in metropolitan markets should not be compelled to access their news programming online, as suggested in the introduction to the majority decision. Not all Canadians can access news and information content on online platforms in major centres for a variety of reasons.

Adding to the bite of the minority’s critique is that the Commission’s Notice of Consultation only raised the possibility of digital/linear sharing of Canadian programming expenditures provided that exhibition on linear television remained protected by licence conditions.

And it was not as if the CBC was asking for these regulatory innovations. Lafontaine listed all of the long-standing licence obligations that the public broadcaster applied to renew or tweak, but were struck down by the majority anyway:

- Broadcast of Canadian programming: the conditions of licence for the broadcast of a predominance of Canadian programming on the Corporation’s English- and French-language conventional networks and television stations as well as its three discretionary services ICI ARTV, the documentary Channel and ICI EXPLORA.

- Broadcast of French-language local programming in the metropolitan market of Montréal: the condition of licence for Radio-Canada’s conventional television network and station to broadcast a minimum number of weekly hours of French-language local programming, most of which is news programming, in the metropolitan market of Montréal.

- Broadcast of English-language local programming in metropolitan markets across the country: the conditions of licence for CBC’s English-language conventional television network and stations to broadcast a minimum number of weekly hours of English-language local programming, most of which is news programming, in the metropolitan markets of Calgary, Edmonton, Ottawa, Toronto and Vancouver, as well as in the English-language OLMC of Montréal.

- Broadcast of French- and English-language independently produced Canadian programming: the conditions of licence that provide minimum requirements for the broadcast of French- and English-language Canadian independently produced programs on CBC/Radio-Canada’s conventional television stations (networks and stations), ICI ARTV and the documentary Channel.

- Broadcast of programs of national interest in peak time: the conditions of licence for the broadcast of programs of national interest (PNI) during the peak viewing hours of 7 p.m. to 11 p.m. on CBC’s and Radio-Canada’s conventional television networks and stations, and the requirements regarding the broadcast of Canadian independently produced PNI content.

- Broadcast of French-language children’s and youth programming: the conditions of licence for the broadcast of French-language Canadian children’s and youth programming by Radio-Canada (conventional network and stations) in Quebec and across Canada. The conditions of licence include the obligation for Radio-Canada to broadcast at least 15 hours per week of Canadian programming for children under the age of 13, and the obligation for Radio-Canada to broadcast original Canadian French-language children’s and youth programs.

- Broadcast of English-language children’s and youth programming: the condition of licence for the broadcast of 15 hours per week of English-language Canadian programming on CBC’s conventional television network and stations aimed at children under the age of 13.

- Broadcast of original and original first-run Canadian programs: the condition of licence for Radio-Canada’s conventional television stations to broadcast original French-language Canadian children’s and youth programming, and the obligation for the documentary Channel to license from independent production companies not less than 75% of its original, first-run Canadian content hours.

- Broadcast of Canadian feature films once per month on CBC: the condition of licence for the broadcast of one Canadian feature film during each broadcast month on the CBC’s conventional television network and stations.

In so many words, Lafontaine accused the majority of blindsiding everyone including the Canadian public to whom the Notice of Consultation was issued in 2019.

So the question remains, why did majority take these exceptional steps?

Surely the majority Commissioners know that whatever is left unprotected by a condition of licence is vulnerable to cost cutting, budget cannibalization or defunding.

The Corporation’s Parliamentary funding is $1.3 billion out of $1.8 billion total revenue and has remained stable during Justin Trudeau’s run in the Prime Minister’s office (in fact the Liberals boosted the grant by $150 Million in 2017).

But under a Conservative administration that seems likely to change.

The CPC 2021 election platform did not hide its intentions to gut the CBC English network while protecting CBC North and Radio-Canada:

CBC and Radio Canada have made important contributions to Canada over the past 84 years. While parts of it remain as relevant as ever, including Radio Canada, CBC Radio, and CBC North, many question whether CBC’s English TV continues to live up to its mandate. There are also concerns that CBC’s online news presence is undermining the viability of Canadian print and online media, reducing the diversity of voices available to Canadians.

Canada’s Conservatives will:

* Give Radio-Canada a separate and distinct legal and administrative structure to reflect its distinct mandate of promoting francophone language and culture while maintaining its funding and providing for continued sharing of resources and facilities where applicable…

*Protect CBC Radio and CBC North

*Review the mandate of CBC English Television, CBC News Network and CBC English online newsto assess the viability of refocusing the service on a public interest model like that of PBS in the United States, ensuring that it no longer competes with private Canadian broadcasters and digital providers.

Ongoing Conservative political messaging about “CBC bias” and “defunding the CBC” has become so routine its almost goes unreported.

The absence of licence conditions on the major local stations removes an important obstacle to implementing deep budget cuts.

So the answer to the question of “why” must be a compelling policy reason to remove those safeguards. You won’t find it in the majority ruling.