CHCH News Director Greg O’Brien

March 8, 2026

Just before the new year, the CRTC hit the pause button on its staff investigation into Meta’s leaky ban on news content posted to Facebook and Instagram, declaring a wait-and-see.

CRTC VP Broadcasting Scott Shortliffe issued the brief notice on December 3, 2025, noting Meta’s efforts to remove user posts of Canadian news and stating that the Commission would continue monitor the news ban.

On February 4th, the LITS coalition of 15 independently owned television stations filed an application to the CRTC asking the regulator to confirm that Meta, despite its news ban announced in August 2023, continues to “make news available” in Canada through either the replication of news content or linking to it on Facebook and Instagram. The broadcasting companies, which include Hamilton’s CHCH and Victoria’s CHEK, want the CRTC to order Meta to bargain with news outlets.

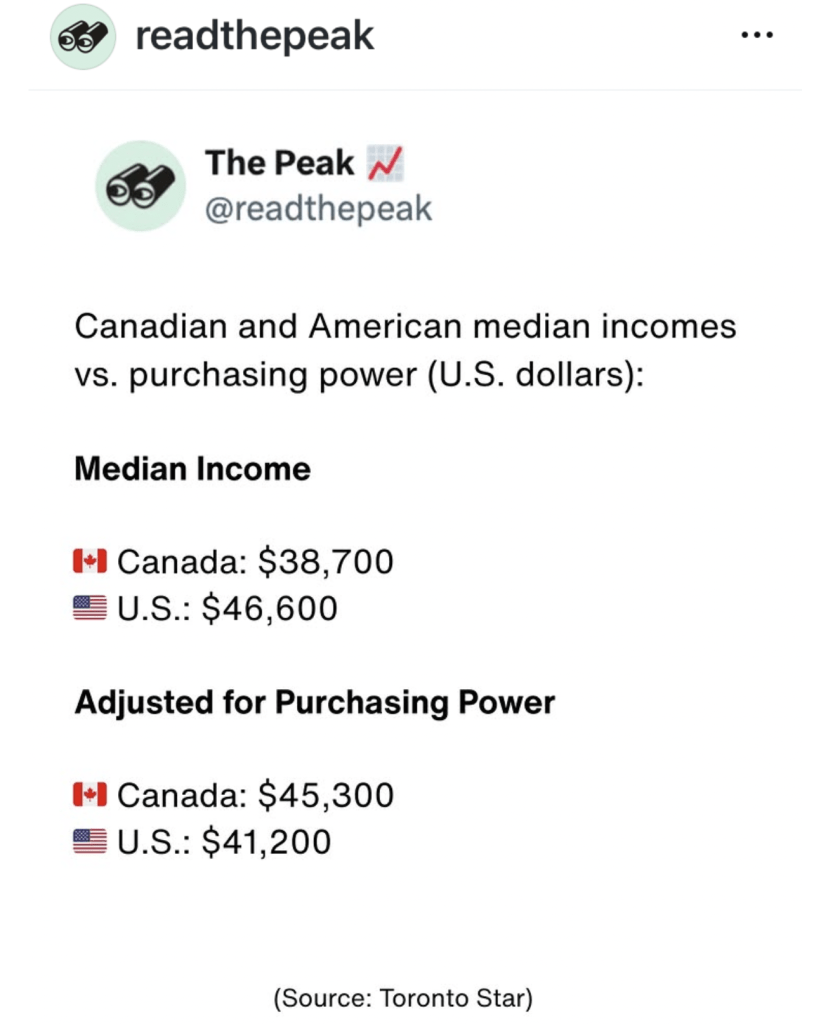

MediaPolicy wrote about this issue previously here and here, pointing out the regular news posting activities of Canadian digital outlets Telelatino, The Peak (on Instagram but not Facebook) and Narcity on both platforms.

Narcity publisher Chuck Lapointe claimed in a LinkedIn post to have an agreement with Meta to exempt his publication from the news ban.

Aside from these exempted news publishers, the LITS application to the CRTC cites a long list of news posts from Meta user accounts, often linking back to content posted on YouTube. The application offers the CRTC a number of examples of user-posted content from news sites that directly compete for audience with digital content published by the television stations on their websites. According to LITS, some of the posts were removed after several months, others remain.

CHCH News Director Greg O’Brien also points to Facebook permitting regular posting of video clips from the Rogers City-TV Breakfast Television morning show in Toronto, in direct competition with CHCH’s own morning show.

It’s a legality worth noting that the Online News Act does not narrowly define the “news content” that Meta must bargain for as hard news or political reporting. The Act describes news content as original reporting on “matters of general interest and reports of [Canadian] current events, including coverage of democratic institutions and processes.”

Asked why he thinks Meta is platforming CityTV’s Breakfast Television but blocking CHCH, News Director O’Brien said “we can’t understand this and can get no answers from Meta. Breakfast Television and [CHCH] Morning Live are competing morning news shows. We are banned from Instagram and Facebook and BT is not. It makes no sense and is unfair. Global Television’s morning show also has an Instagram page. It makes me think Meta has some side deals with them.”

LITS counsel Peter Miller expressed a similar concern when asked why it was the small independent television stations raising this issue with the CRTC on their own, so far.

“It’s also possible that Meta has done deals with large players. Certainly the recent stance [Meta has] taken with government —-drop the [Online News] Act and we’ll do deals that include [licensing of] AI—- suggests they’d rather only have to concern themselves with bigger news players. And the survival of smaller independent players and news media diversity generally is the most at risk here,” Miller told MediaPolicy.

Further details of LITS allegations can be downloaded below.

***

Another day, another controversy for CBC/Radio-Canada.

The Corp’s decision to broadcast its 24-hours national news television channels on Amazon Prime for a monthly subscription fee has been heavily criticized in the press, Québec’s Culture Minister and by federal and provincial political parties in Québec.

The criticism is that CBC is partnering with a foreign tech platform that is overwhelming Québec audiences with English-language content.

Making it worse, say critics, the same live news content is not available on Radio-Canada’s ici tou.ca (the CBC says that is coming to tou.ca, it’s already available on CBC Gem).

La Presse cultural columnist Mario Girard was so incensed that he speculated he might be unable to defend Radio-Canada funding in the future.

“In short, if we follow the logic of this agreement with Prime Video, Radio-Canada will be selling content (largely paid for by Canadian taxpayers) to an American giant that will, in turn, siphon off profits to further crush Canadian private media,” wrote Girard in his regular column.

CBC content is available on a number of non-Canadian platforms, on its YouTube channels in particular, as the public broadcaster follows the audience leaving, or never considering, conventional television. As well, media content is increasingly discovered on apps that are gated by foreign-owned operating systems installed in smart televisions and other connected devices.

This week the Hamilton-based and Canadian owned online distributor Parrot TV announced it is adding the ad-supported CBC National News Channel, CBC Vancouver and CBC Toronto to its other live news channels CHCH-TV and Newfoundland TV.

Besides the CBC news channels, Amazon Prime also carries live Canadian news channels on paid subscription from CTV, Global, and Rogers City-TV, but not Québecor’s TVA.

***

Bell Media has responded to speculation about its long term licensing of Warner Brothers Discovery’s HBO content on Crave, now that Paramount has won its takeover bid for WBD. In a declaration kept short and sweet, Bell claimed its HBO deal was good for “the foreseeable future.”

Paramount has announced its intention to merge HBO into its own subscription service Paramount Plus and also fold in its advertising supported app, PlutoTV.

The expiry date of Bell’s licensing deal for HBO’s content remains a commercial secret. If I was a shareholder, I would want that secret told.

In the meantime, Bell must be planning to pivot hard to rebuilding its Crave platform into an engine fuelled by its own Canadian IP. There’s an excellent interview of Bell’s content VP, Justin Stockman, by Irene Berkowitz, exploring how Bell hopes to build on the success of hit shows like Heated Rivalry, Sullivan’s Crossing and Empathie.

***

If you would like regular notifications of future posts from MediaPolicy.ca you can follow this site by signing up under the Follow button in the bottom right corner of the home page;

or sign up for a free subscription to MediaPolicy.ca on Substack;

or follow @howardalaw on X or Howard Law on LinkedIn.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME. But be advised they are public once I hit the “approve” button, so mark them private if you don’t want them approved.

I can be reached by e-mail at howard.law@bell.net.

This blog post is copyrighted by Howard Law, all rights reserved. 2026.