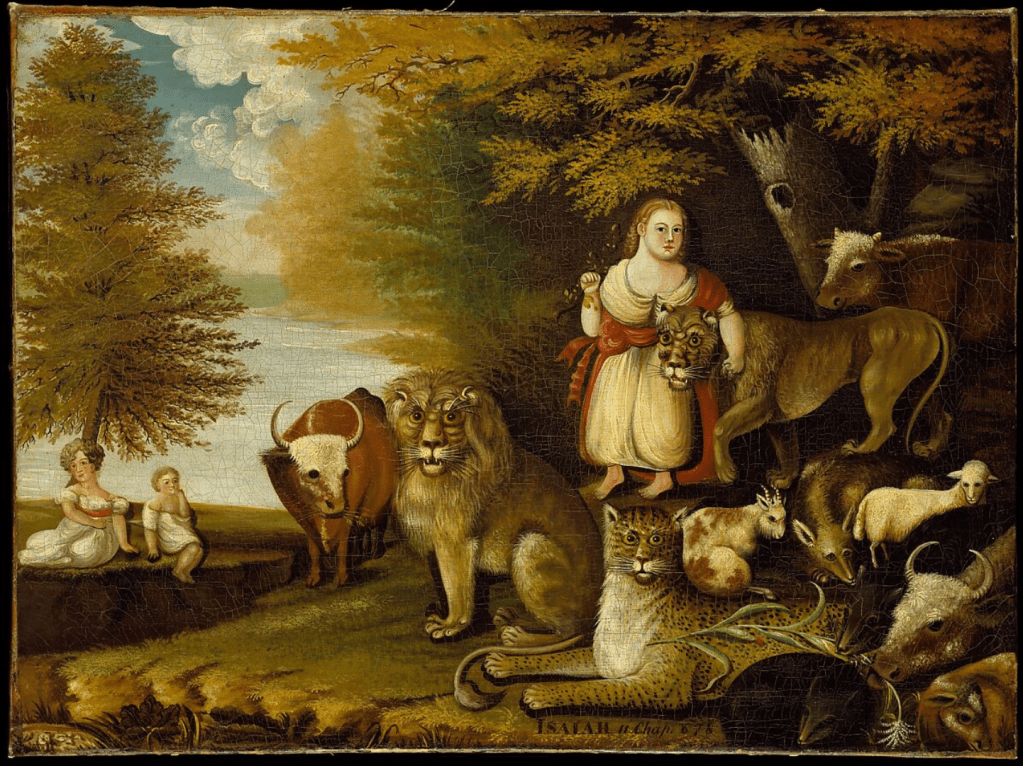

“The Peaceable Kingdom” (Painting by Edward Hicks, c.1832) – cover art from Will Klymicka’s book Multinational Citizenship

July 15, 2024

The goals of Canada’s Broadcasting Act, updated by the Online Streaming Act Bill C-11, tell us a lot about who we are.

The bill has a long list of policy justifications for involving the state in cultural creation and discovery, beginning with the mission “to serve to safeguard, enrich and strengthen the cultural, political, social and economic fabric of Canada.”

In other words, we regulate media for the betterment of Canada, not solely to satisfy the individual appetites of Canadian consumers.

What are we, Canada? Answer: a liberal democracy engaged in a never ending conversation about a society based on the individual rights and freedoms entrenched in our 1982 Charter and, on the other hand, the rights of provinces, language communities, and Indigenous peoples inscribed in the 1867 act of confederation, treaties, territorial claims and the Charter.

The dialogue about who we are takes place as much in Tim Horton’s as it does in the House of Commons. The artistic rendering of who we are takes place in mass media, as does the political debate. The Broadcasting Act regulates some of that mass media: video and audio news, sports and entertainment programming.

Lately, the legislation has been hotly debated, questioned, misrepresented, doggedly defended or just plain misunderstood. In my book on Bill C-11, Canada vs California, I wrote about the mechanics of broadcasting regulation, but also I offered thoughts on why both supporters and critics are drawn to debating it. I posted an earlier version of that chapter, “Telling Canadian Stories,” on MediaPolicy.ca.

There’s yet another angle on explaining our riveted attention to media regulation and, believe it or not, it’s liberal rights theory.

Yup, liberal rights theory and media regulation. You roll your eyes.

Stay with me for a moment.

The reason why the connection between liberal philosophy and the Broadcasting Act is more relevant than might first meet the eye is that Bill C-11 has become a flashpoint for a culture war between the governing Liberals and the Opposition Conservatives.

The bill didn’t start out that way. In fact the Conservatives initially supported the bill when it was tabled in the House of Commons in 2020 by the governing Liberals as C-10. Conservative MPs said the bill was long overdue and that the Liberals’ attempt at updating the Broadcasting Act might be too cautious. At the time, Conservatives supported regulating YouTube and other big content sharing platforms.

It wasn’t surprising that at first Liberals and Conservatives were on the same page about the bill: they had shared more common ground than they had disagreement on the Broadcasting Act, dating back to 1968.

That changed very suddenly in 2021, as I map out in my book. Soon enough Pierre Poilievre swore to “kill the bill”. As a consequence, some version of deregulating Canadian broadcasting is sure to find its way into the next Conservative Party election platform. The Conservative messaging in its opposition to C-11 is currently so libertarian, so hostile to any state regulation of media, that it appears to endorse a wide open global market for cultural content without any special rules to foster Canadian content.

How liberal rights theory fits into all of this is that the cultural mission operationalized by the Broadcasting Act —-which is resisting the market power of American programming by subsidizing and promoting Canadian content—- is in fact an act of small “l” liberalism. And dare I say, in the end as Canadians we are all liberals. Fundamentally we agree upon this: that all Canadians are equal to each other as human beings. That is the taproot of liberal rights.

If so, as liberals we ought to be able to agree on many shared values in cultural legislation, even if we disagree on many points of their application through regulatory activity.

Now what I know or can explain about liberal rights theory, especially as it applies in the real world to cultural legislation, could fill a thimble.

But the writings of renowned Canadian political theorist Will Klymicka are a guide to how to do this.

During the 1990s, Klymicka published a robust theory of liberal rights, as distinguished from the minimalist version offered by students of the great 19th century philosopher Jon Stuart Mill. He was writing at a time of great uncertainty, including genocidal violence, between national majorities and minorities in Yugoslavia and Rwanda. And of course, in the same time frame Québec came within a referendum whisker of leaving Canada.

Klymicka’s project was to explain a theory of minority cultural rights within the framework of a liberal society, a creed that he believed already existed but was poorly articulated.

The starting point of any liberal society will always be the familiar set of personal liberties but, Klymicka wrote, it has to move on from there to build political institutions that mitigate the inevitable cultural domination of the majority “nation” over minority nationalities, ethnic communities and equity-seeking groups. That’s important, he wrote, because the liberal conception of human freedom is about choice, including the freedom of individual members of minority groups to consume culture that is especially meaningful to their pursuit of a good life. The hard-line liberals, such as J.S.Mill, demanded that minority groups assimilate into the majority and, to make that a credible demand, fell back on disparaging minority culture as parochial, illiberal or backward looking.

You may have guessed that Klymicka never considered the application of his writing to Canada’s cultural legislation which stresses the importance of minority culture on two levels.

The first is making breathing room for the culture of English-Canadians as a minority within an American dominated continental market for cultural goods.

The second is creating the same space for the culture of French-speaking Canadians, Indigenous peoples, anglophone minorities, and other domestic minority groups hoping to protect their mass media culture from domination by English-speaking and other majoritarian cultural content.

When you describe the goals of the Broadcasting Act as the pursuit of those public policies, I believe that most Canadians, and most Canadian political parties, see it the same way. The devil is in the details of applying the principles. I speculate, with a careless disregard for taboos, that what roils the debate is the single-minded devotion (and success) of the Québec political class in using the Broadcasting Act for one of the things it was designed to do: strengthen the ability of Québec to protect its French language culture.

Not everyone will read Klymicka’s manifesto, Multicultural Citizenship (Clarendon Press, 1995). It’s dense stuff with a $100 cover price (and not easily available from public libraries). As the next best thing, I recommend Andy Lamey’s The Canadian Mind, an engrossing anthology of essays that includes a chapter on his mentor, Klymicka.

***

If you would like regular notifications of future posts from MediaPolicy.ca you can follow this site by signing up under the Follow button in the bottom right corner of the home page;

or e-mail howard.law@bell.net to be added to the weekly update;

or follow @howardalaw on X or Howard Law on LinkedIn.

2 thoughts on “Hail Bill C-11: our Canadian common ground”