Mark Carney is due for a follow up to his 2021 book Value(s)

June 29, 2025

I start this week with a recommendation, but not Mark Carney’s first book Value(s) (2021).

Instead it’s book publisher Ken Whyte’s latest Substack post cuffing the Prime Minister for cutting a deal for his unreleased second book with an American publisher.

Aside from the PM striking this discordant note during a trade war, it’s inviting to contrast the Liberals fighting the good fight for Canadian broadcasting and news journalism to their neglect of book publishing where foreign publishers claim 95% of Canadian sales and 98% of profits.

To be fair, book publishing lies outside of federal regulatory jurisdiction and many of the titles printed by Canadian book publishers are subsidized by federal Canada Council grants and the Canada Book Fund.

Still, I have to sign on to this statement from Whyte:

There aren’t many silver linings to Trump’s second term, but one has to be that it has highlighted the perils of outsourcing so much of our economy and culture to the US. We were lulled into a cultural complacency, thinking it didn’t matter that another country’s norms, values, and market demands dominated our markets and our discourse.

***

Speaking of “outsourcing our culture to the US,” doing something about it is the CRTC’s full time job lately.

The Commission is almost done public hearings on yet another file implementing the Online Streaming Act. This one’s inscrutably labelled “market dynamics.” It’s about getting the big players in distribution to bring Canadian content to market.

Not a sexy policy issue compared to defining Canadian content or ordering foreign streamers to pony up $200 million for Canadian media funds. But crucial.

In the Market Dynamics proceeding, the Commission is revisiting its expectations of cable companies to distribute Canadian content and then doing the same for online distributors like Roku, Amazon and PlutoTV.

It’s the Commission’s job to sniff out the danger of big distributors exploiting their gatekeeper power over smaller content programming companies. Unchecked, this chokepoint market power can stifle cultural competition and the survival of independent Canadian broadcasters.

It’s a messy file because the related policy problems of market power in distribution and cultural gatekeeping by distributors bleeds into two other CRTC files focussed on Canadian content obligations for online television broadcasters like Netflix and music streamers like Spotify.

What unites all three CRTC proceedings is the holy grail of “discoverability”: making Canadian content prominent for Canadian audiences so they consume it.

There’s a long list of what prominence means in an online environment.

It might include marketing campaigns, event sponsorships, online fan pages, favourable home screen positioning for Canadian shows and playlists, “For You” recommendations, and even ranked outcomes in response to content searches. In other words, something better than the ghettoized “Made-in-Canada” menus on offer, heavily populated with titles that frequently aren’t Canadian by any definition.

Based on their legal filings, the global giants are opposed to any regulated prominence for online Canadian content. They plead the uniformity of their platforms across a global audience and their pursuit of a frictionless connection between platforms and subscribers. Regulation, as they see it, is someone else choosing your clothes for you.

The Canadian Association of Broadcasters retorts that the reality is that online programming is bought, sold and distributed on market-by-market basis around the world and platforms are not global monoliths. That means unique Canadian requirements can be customized to each global’s “dot ca” Canadian streaming services.

In filings to the CRTC, cultural advocate Friends of Canadian Media has sketched out a regulatory scheme in which the Commission assigns online distributors a target CanCon budget of 30% of their Canadian revenues. That commitment can be satisfied by the cash and prominence value of commercial deals with the Canadian programmers they put on their platform. There’s already a down payment on the 30%: the Commission’s 2024 ruling that foreign online undertakings fork out 5% cash contributions to Canadian media funds.

The Friends proposal mirrors what the Commission previously said it has in mind.

In its very first public pronouncement on implementing the Online Streaming Act in May 2023, the Commission identified prominence rules as the non-cash component in each streamer’s regulatory load. Prominence efforts would be assessed a monetary value as a supplement to cash investments in Canadian programming.

Whatever these three Commission rulings end up saying in broad strokes about discoverability, the detailed prominence rules for each streamer or online platform are supposed to be nailed down by the Commission in yet another regulatory phase that won’t even begin until 2026.

But the prominence of online Canadian content is only part of the cultural gatekeeping problem, and not the most difficult for the Commission.

Before prominence comes “access.” Canadian audio and video programmers that are big (Bell, Rogers or Québecor), medium-sized (e.g. Stingray or Corus) or small (e.g. APTN or OneSoccer) first have to elbow their way onto crowded distribution platforms and get paid a fair market rate by distributors or else they needn’t trouble themselves about prominence.

As Corus stated its filing, it’s unrealistic for Canadian programmers to go solo with their own streaming apps as a core business model.

If the online streaming step-outs launched by Canadian broadcasters are too small to go toe to toe with Netflix and the Hollywood streamers, that makes the alternative ——getting on global distribution platforms like Roku and Amazon—- increasingly indispensable as Canadians shift from cable to streaming. That puts the distributors in the driver’s seat in any negotiations over prominence and compensation of Canadian broadcaster content.

If this problem of market power in online distribution has a familiar ring to it, it should.

For the last two decades the same power game has played out between Canadian cable companies and Canadian broadcasters over access, prominence and compensation.

In 2011 the Commission responded with a Wholesale Code setting out rules of fair play, enforceable through Commission orders for access and prominence as well as binding arbitration over commercial rates for distributor payments for programmer content. The Code was revised and strengthened in 2015 and tweaked again when the Commission approved the Rogers-Shaw merger in 2022.

Ever since, commercial fist fights have broken out and, in the public eye, play out as David and Goliath stories. Litigation before the Commission abounds.

The large cable distributors Bell, Rogers, Telus and Québecor are often accused of bullying Canadian programmers, threatening to kick them off the cable dial for audience underperformance, whether real, imagined or exaggerated.

Programmers see it all as a cynical bargaining ploy to renew expiring commercial deals at lower rates of compensation.

In turn, the cable companies routinely accuse programmers of gaming the regulatory system by manipulating the fair play rules to hold on to expiring commercial rates negotiated during better times in the industry.

The Wholesale Code’s fair play rules are up for inspection in the Market Dynamics proceeding. The big Canadian companies want the rules either heavily edited (Québecor and Bell) or gutted (Rogers).

The Canadian programmers are defending the Wholesale Code. They have allies in second-tier Canadian cable companies, such as the Nova Scotia based Bragg Communications and the Montréal-headquartered Cogeco, who believe the big Canadian broadcasters make them overpay for the programming that audiences want in their cable package.

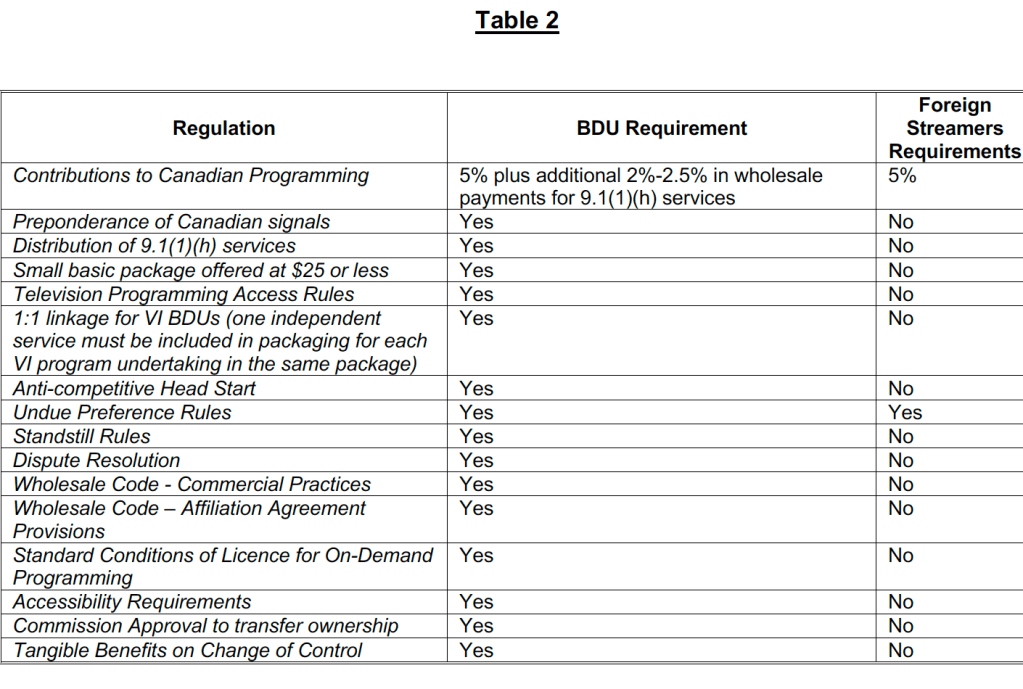

The programmers also want the spirit of the fair play rules to be mapped over (see Bell’s chart below) to online distribution by the global giants and, now that Rogers operates its Xfinity platform for streaming apps, their Canadian imitators too.

It’s an uphill if not impossible regulatory battle for Canadian programmers.

In a strange move that they never properly explained, the Trudeau Liberals hamstrung the Commission when writing the Online Streaming Act by withholding the Commission’s key lever to impose binding arbitration on online distributors.

But other regulatory powers over online access and distributor favouritism remain intact, at least in the legislation and perhaps soon in CRTC regulations.

If the Commission trains are running on time, we’ll get a ruling on Market Dynamics in late 2025.

[Disclosure: I am a volunteer member of Friends of Canadian Media’s policy advisory committee. The Friends proposal above wasn’t my idea, but as Kim Mitchell might say “damn, I wish I wrote that.”]

***

One of the more tone-deaf utterances offered by Netflix during CRTC proceedings was that it doesn’t need to be told to make Canadian content more prominent on its service, because entertainment writers at Canadian news outlets are doing the job of promoting CanCon so well.

Nevertheless, here’s a sincere MediaPolicy shout-out to the dwindling corps of Canadian journalists regularly reviewing a global ocean of content and spotlighting great Canadian shows and music.

And here’s a gold star and thanks to the writers at the Globe and Mail who, after consulting with other critics far and wide, just put together a song playlist from their top 100 Canadian albums. There’s a handy gizmo: you can upload it to your Spotify account.

And don’t forget: our homegrown bands will front Canada Day celebrations on Tuesday, broadcast or streamed on CBC.

***

If you would like regular notifications of future posts from MediaPolicy.ca you can follow this site by signing up under the Follow button in the bottom right corner of the home page;

or sign up for a free subscription to MediaPolicy.ca on Substack;

or follow @howardalaw on X or Howard Law on LinkedIn.

I can be reached by e-mail at howard.law@bell.net.

This blog post is copyrighted by Howard Law, all rights reserved. 2025.

Rich blog. Much to think about. And a good antidote after a week in DC. Thanks.

>

LikeLike