September 17, 2021

If the next federal government makes Google and Facebook contribute to Canadian journalism, the big question is how.

The Liberal election platform is aggressive: in the first 100 days of a new mandate, Ottawa will legislate the same collective bargaining regime between the Platforms and news organizations as was adopted in Australia.

The Conservative platform touts a royalties-for-news scheme adopted in France and recently tabled by the Tories in the Senate. Newsmedia Canada estimates the Platform payment per journalist in Australia at about $CDN 50,000 compared to $7500 in the French scheme. The CPC platform references “best practices” from both countries.

None of the major political parties are advocating for a News Fund similar to the many we already have in Canada supporting weekly newspapers, newscasting by independent television stations, and journalist salary subsidies for daily newspapers. The Heritage Canada consultation on Platform contributions to journalism showed interest in a News Fund, but the consultation has apparently been eclipsed by the election promises of both the Liberals and the Conservatives.

Without a doubt, the “Australian model” is by far the most successful effort by sovereign nations to challenge the power of Big Tech.

It legalizes collusive bargaining groups of news organizations and forces Google and Facebook to negotiate a fair deal on payment for news with each group. No deal is done until each news group gets one, so the Platforms can’t engage in divide and conquer tactics, picking favourites or stonewalling other publishers. And most importantly, fair payment is guaranteed by access to final offer (so-called “baseball-style”) binding arbitration.

The policy virtue of the Australian model is unambiguous: the Platforms must pay for news content.

Like any journalism media, the Platforms draw readers and advertisers with the promise of good material, whether you read it all or not. Accordingly, the Australian legislation requires the bargaining parties (and arbitrators) to take into account the direct value of a news organization’s content that gets read, but also the indirect value of content you pass over and decide not to read. This applies both to Google’s Search results and your scroll through Facebook’s News Feed.

The Australian model also has some practical advantages over other solutions. Once legislated, the negotiations between news organizations and Platforms are completed in a few months or less. The bargaining and arbitration regime doesn’t involve government so it doesn’t attract swarms of critics and opportunists denouncing government meddling in the media.

Newsmedia Canada believes the Australian model will deliver up to $620M annually to news publishers, compared to $95M per year from the federal government’s aid to journalism program. More than a band-aid, that kind of cash injection should mean more reporters and more coverage.

Yet despite the Australian model’s advantages, there are limitations and flaws.

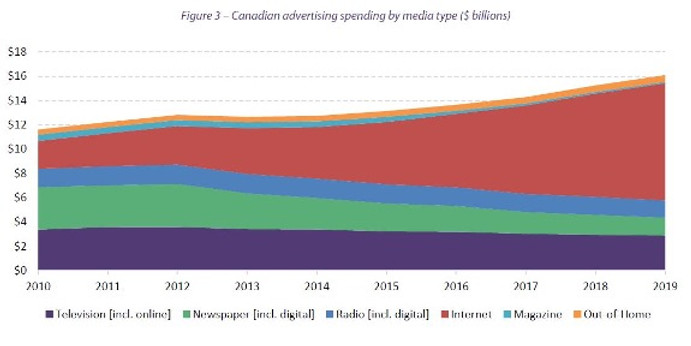

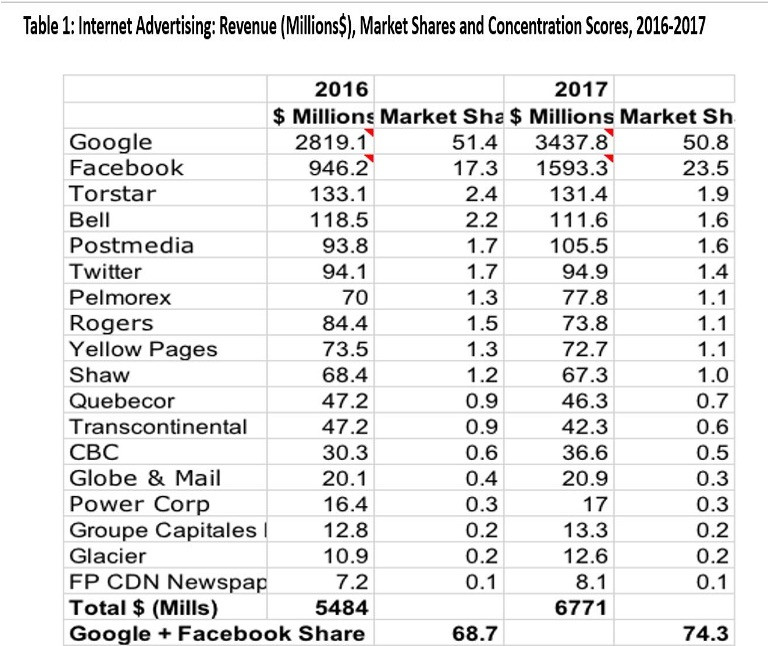

The exclusive focus on paying for news content —-ignoring the Platforms’ dominant monopoly over the advertising revenue that historically paid for news – invites the Platforms to engage in hair splitting over the value of the news they monetize.

While the Platforms blinked in Australia and settled with news organizations to avoid arbitration (a rebuttal to skeptics of whether the Platforms profit from news content), they may still choose to fight it out at arbitration in Canada. Throwing the future of Canadian journalism into the hands of an arbitrator is a high-risk gambit considering the public interest in a solvent business model for journalism.

Another limitation of the Australian model is that the negotiated deals are shielded from public view (unless the government legislation says otherwise) and provide no rules about what kind of journalism is being aided. In a private commercial deal, the news organizations can spend their cash on anything they like. Including executive compensation.

In other words, what’s lacking in the Australian model is the primacy of the public interest in an informed citizenry, the justification for government intervention in the first place.

The straightforward way to put the public interest first is with a News Fund, distributed to news organizations on a transparent basis, with Google and Facebook paying their share at a government-fixed tariff.

We did something exactly like that in 2019: the federal assistance to news journalism legislated by the Liberals enacted a $14,000 per journalist wage subsidy for all professional written news organizations, otherwise known as aid to Qualified Canadian Journalism Organizations.

Despite the politicized hysteria about government intervention in media, the end of democracy and so on, the highly transparent QCJO program is a success for the news organizations that qualify (which excludes broadcasters), though not enough money to stem the loss of news coverage. In the intervening two years since 2019 you may have noticed the complete absence of scandals or complaints about the program’s administration. If the newly subsidized Press has suddenly gone soft on the ruling government, no one has been able to point that out.

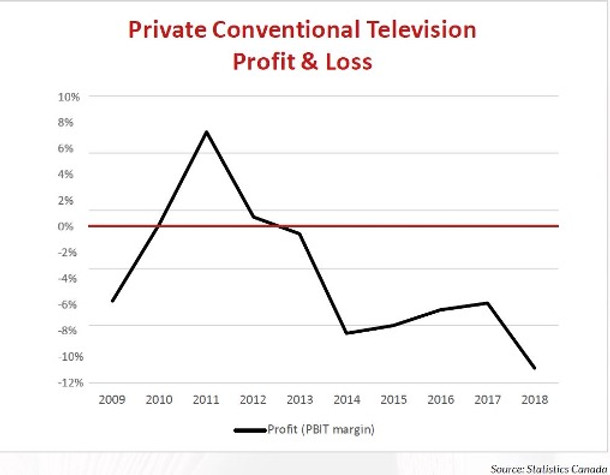

There are other public news funds too. In 2017 the CRTC mandated a $20 million per year subsidy for struggling local news stations. The Independent Local News Fund is financed and administered by the industry’s cable companies. No scandals, no complaints.

There is also the long-standing Canadian Periodical Fund providing modest subsidies to magazines and community weekly papers, funded and administered by Heritage Canada. Again, no scandals, no complaints.

Ditto the federal Local Journalism Initiative set up by the federal government in 2017 and administered by News Media Canada. With a modest $10 million per year, the LJI creates 342 temporary journalist positions in the most under serviced local communities. No scandals, no complaints.

Primary in all of these News Funds is the public interest. Clear and transparent rules are set for what kind of news journalism deserves public support. Either taxpayers or companies finance it at contribution rates set by regulation, and government is accountable for the integrity of its administration.

In fact, there is an opportunity at this point in our history to combine a number of these funds into a publicly accountable, arms-length super-news fund with mixed private-public funding from governments, Google, Facebook, our Canadian cable companies, and philanthropic donors.

In addition to the public interest of keeping news organizations alive, a News Fund model that mandates contributions from Google and Facebook has the added benefit of holding the Platforms accountable for the monopoly harm of hoarding advertising dollars and failing to share them reasonably with Canadian news media. This is something the Australian model doesn’t do.

And what’s interesting about creating a News Fund to mitigate the harm caused by the Platforms’ monopoly over digital advertising is that as a matter of public policy we are already half way there.

One of the Liberals’ 2021 Budget measures that flew below the political radar was a Digital Services Tax on foreign tech companies, set for now at 3% of their Canadian revenue. Scheduled to become a $900 million contribution to federal coffers by 2025, the DST is explicitly a “digital audience” tax. Big Tech, which includes Google and Facebook as the third and fifth wealthiest members of that elite club, is required to pay the government for gathering and monetizing the private data of Canadian citizens.

You will have quickly deduced that the DST money, even the share paid by Facebook and Google, doesn’t go to Canadian media. It goes to the federal government. But, a willing Ottawa could earmark at least part of the DST for a News Fund, just as it earmarks a CBC Parliamentary grant.

The DST may or may not be a permanent feature of federal landscape, though both the Liberals and the Conservatives support it. For now, the Ministry of Finance is describing it as an interim measure until international talks on a minimum corporate tax for offshore businesses reach an agreement. At that point, the DST would lose its unique character as an audience tax.

Advocating for a News Fund and a media-dedicated DST may end up amounting to no more than an interesting policy debate. Neither the Liberals nor the Conservatives seem to be interested for now. Like a lot of things in play during this federal election, we are going to have to wait until the next Throne Speech to see whether the next government is going to hold the Platforms to account and save local news.

And if this hadn’t been dragging on for the last five years you could almost be patient. As Canadian news organizations continue their financial decline, the question may not be how, but now.