October 12, 2022

During Heritage Committee hearings on Bill C-18 on September 27th a skeptical Kevin Waugh (CPC- Saskatoon-Grasswood) questioned whether the FaceGoogle-Pay-For-News legislation would do anything for rural publishers.

Testimony from Chris Ashfield, the publisher/editor of Saskatchewan’s Grasslands News group of five local weeklies, tapped into a deep concern previously documented by TMU’s News Poverty Project about the troubling spread of news deserts in rural and suburban communities.

Ashfield told Heritage MPs how the publications in his local chain and other Saskatchewan weeklies are shrinking in advertising revenue, news coverage, and the number of employed journalists.

The latter could be a barrier to rural publishers seeking access to the compensation expected to flow from C-18. Currently the eligibility criteria in s.27(1)(b)(i) requires a publication employ at least two journalists, excluding the publisher, other staff and freelancers.

Asked about that rule, Ashfield told MPs:

In Saskatchewan, the outcome [of the two-journalist rule] would be fairly detrimental to a lot of the smaller publications. The newspaper industry has changed. Most of the work is now being done by the publishers, who are multi-tasking.

In my own operation, I run five newspapers, but each newspaper has anywhere from a part-time reporter to one full-time reporter. Under the current situation, we would not qualify for that…

Communities are on the verge of losing their newspapers and with them the coverage of their municipal councils, school boards, sports and cultural events and all the independent local news coverage residents have relied on for decades.

The growth of news deserts and the parched news coverage that results is without a doubt an alarming development for the Canadian news ecosystem and the democracy it sustains.

In its annual report released last week on the dire state of local news in the United States, the Northwestern University Medill Journalism School observed that communities in news deserts, or reduced to only one publication, skew towards a poorer, older and less educated demographic. They are also far less likely to be patronized by philanthropic donors or journalism programs, or by digital news start-ups, all of whom gravitate towards urban centres and state capitals.

Even were we to ignore these news deserts as someone else’s problem, say the authors of the report, there is a knock-on effect on the entire polity:

In a healthy news ecosystem, the journalists at local print and digital news organizations not only cover the ebb and flow of everyday life in their communities, but also alert reporters at national and state newspapers, regional television stations and larger digital operations to developing trends and major occurrences that deserve broader attention. Journalists at these larger organizations, in turn, produce the majority of the investigative and beat reporting that prompts legislation and policies to correct problems. As cracks form in the base and local print and digital news outlets struggle to gain traction or disappear, the journalism of the national and state news organizations is also compromised.

The Medill Report continues its year-by-year documentation of the decline in news publishing. The metrics of that decline in the US are supported by more granular data than are available in Canada due to the size of the market. The key and most reliable metric is the decline in journalism employment: down 60% nationally among dailies and weeklies since 2005.

Neither are digital publishing start-ups a saviour: the Report says their growth is incremental, dwarfed by the size of decline in conventional media, and in any event not taking root in news deserts.

The size of the US market provides more opportunities for experimentation: the Report cites encouraging examples of collaborative news coverage and shared overhead among publishers.

Financial aid to journalism also looks different in the US than Canada: the US is more advanced in private philanthropy and non-profit activity while remaining far behind Canada in terms of government aid. In addition, it’s not clear as yet if the American counterpart to Canada’s Bill C-18 will get through Congress.

In Canada, the flow of C-18’s anticipated journalism funding to small weeklies will be influenced by a number of legislative design factors including the two-journalist requirement.

The paid weeklies are already eligible for discretionary funding from Heritage Canada through the little-known but decades-old Canadian Periodical Fund/Aid to Publishers program. The free weeklies are eligible for similar funding under the Special Measures for Journalism program which began as Pandemic funding and has been extended for three years by the 2022 budget. In either program there is no requirement for a minimum number of employed journalists (only that the publication “regularly present written editorial content from more than 1 person.”)

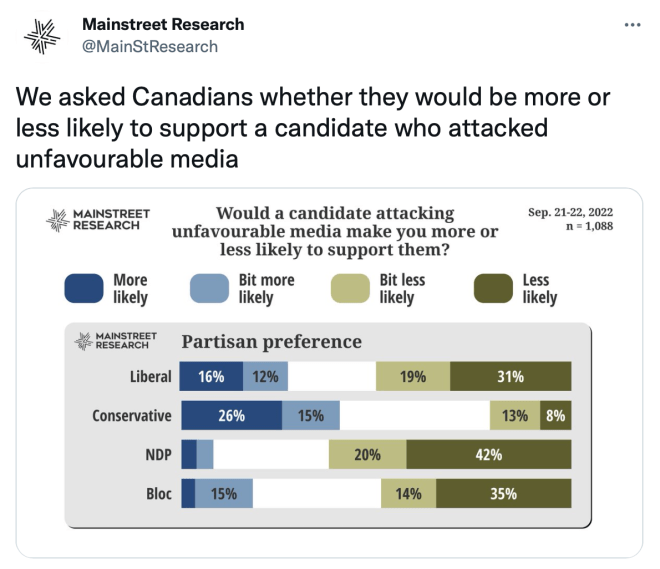

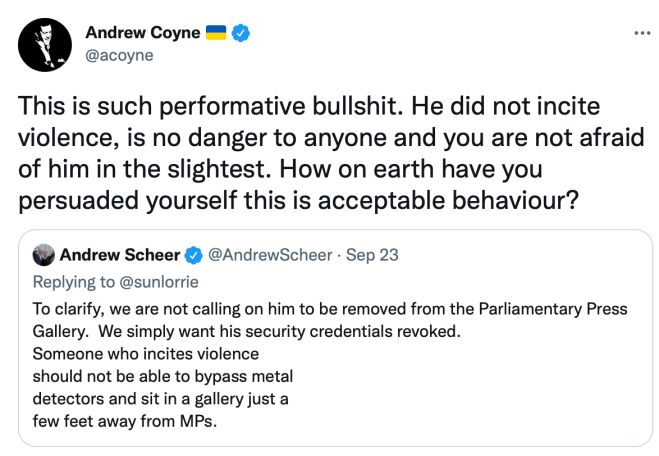

There is however a public appetite for rigorous accountability in the funding of journalism as we saw in the hair-on-fire politics ignited by the federal government’s introduction of aid to Qualified Canadian Journalism Organizations in 2019. As it turned out, the government’s delivery of that program through an arm’s length committee worked out rather well.

It was the QCJO program that introduced the two-journalist threshold. As one eligibility criterion in a long list, the two-journalist rule was probably intended as a barrier to political action groups and basement bloggers accessing the QCJO program. This may be why the newsroom employment threshold found its way into C-18.

However the safety-features of the QCJO eligibility rules were designed with the reassurance that small weeklies like those published by Grassland News’ Chris Ashfield were already drawing government assistance under Canadian Periodical Fund/Aid to Publishers (and they could not draw from both federal programs for the same publication).

There may be amendments tabled by Heritage MPs on the two-journalist rule in C-18’s section 27 which would bring it in line with the Aid to Journalism and Special Measures criteria. On the other hand, the legislation establishes the power of the governing CRTC to devise eligibility regulations that could address the issue.

For its part, the advocate for small publishers, News Media Canada, is pushing for more resources through the government’s internship program the Local Journalism Initiative.