Nanos/Globe Poll

April 13, 2024

Politics makes a fool of public policy on any given day.

To prove this theory, you can tune into ParlVu and watch MPs delight in berating Bell CEO Mirko Bibic for two hours, cutting off his answers, and then clipping their performances for their social media accounts here, here and here.

I digress.

Opinion polls also make a fool of public policy, quite often. The latest is a Nanos poll commissioned by the Globe & Mail to take the public’s temperature on the Liberal government’s suite of Internet legislation.

The legislation in question was Bill C-11 (the Netflix Bill), Bill C-18 (the FaceGoogle Bill) and the freshly tabled Bill C-63 (online harms and hate speech).

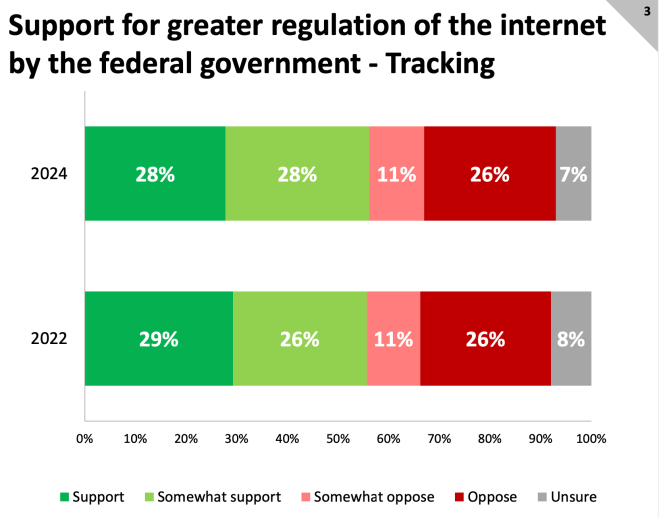

The results were decidedly in favour of Internet regulation: 56% in strong or moderate support with 37% opposed (and 7% undecided).

Here’s the question:

The federal government has proposed a package of laws and policies that would give federal officials new powers to regulate the internet. These include an Online News Act, an Online Streaming Act and proposals to curb online harms such as hate speech. Based on what you have heard, do you support, somewhat support, somewhat oppose or oppose greater regulation of the internet by the federal government?

And here’s what is remarkable about the survey: the results haven’t budged an inch since a poll with the very same question was taken in May 2022.

If you check your calendar, May 2022 was the month in which the controversy over regulating YouTube videos under Bill C-11 was cresting. It was before Bill C-18 was tabled and attacked by critics as a public policy face-plant. The public consultation over the online harms bill generated heat over the government’s initial support for removal of hate posts.

Two years later, there could be many reasons for the public’s constancy despite heated public policy debate over Internet legislation.

It’s a very small portion of the public that educate themselves about the fine points of the bills. Instead many are going with a gut feeling like “censorship is bad,” “Bell is bad” or “Big Tech is bad.” I’m not diminishing the lived experience that leads to such polarization.

On the other hand the public does respond to criticism of the downside risks of government regulation if enough attention is drawn to them. At the same time that public support for regulating the Internet in principle held firm, polls also revealed that critics hit a nerve about regulating YouTubers or triggering Meta’s decision to block Canadian news.

***

So long as it’s still early days in the commercial development of AI large language models we’ll keep getting wild guesses over its trajectory.

The Big Tech companies now have to make a key decision about acquiring more data. It appears that the capacity of AI-LLM to perform miracles may depend on scraping, stealing or buying a lot more copyrighted content.

The question is what decisions about data acquisition are made at this fork in the road. By way of example, it’s been reported that Meta considered buying a major book publisher so that it could feed the content (often licensed from authors for all platforms and uses) to its LLM Venus Fly-Trap.

By way of another example, it’s been reported that Google is thinking of changing its corporate interpretations of copyright and fair use so that they can feed the audio tracks from YouTuber videos to its LLM.

It’s all explained in this New York Times podcast.

***

The financial sustainability of news journalism doesn’t stop being in crisis in between rounds of layoffs.

A valuable part of the public policy discussion is sustainability’s companion crisis: falling public trust in news journalism (and so many other public institutions). What, if anything, can journalists and friends of journalism do about it?

Ivor Shapiro, the retired chair of Toronto Metropolitan University School of Journalism, has something to say about how to rehabilitate public trust in journalism:

Journalists in [many other] countries think it’s simply reasonable in democracies to demonstrate their accountability for standards of factual reporting, and to provide plausible evidence of journalists’ autonomy from the interests of their employers and others.

Yet, these reasonable ideas are practically taboo in historically anglo-Saxon news cultures, for reasons that have more to do with tradition and habit than with common sense or legal rights. Journalists in my generation, especially, have clung with striking self-confidence to inherited habits of news judgment and have largely resisted organizing themselves collectively beyond individual workplaces.

We have refused, in short, to be a profession.

And professionals heed to a code. Shapiro proposes a place to start, here.

***

If you would like regular notifications of future posts from MediaPolicy.ca you can follow this site by signing up under the Follow button in the bottom right corner of the home page;

or e-mail howard.law@bell.net to be added to the weekly update;

or follow @howardalaw on X or on LinkedIn.

Such a good conversation about whether journalists should have a code and self-regulate. The self regulated profession has much to offer as a model.

>

LikeLiked by 1 person