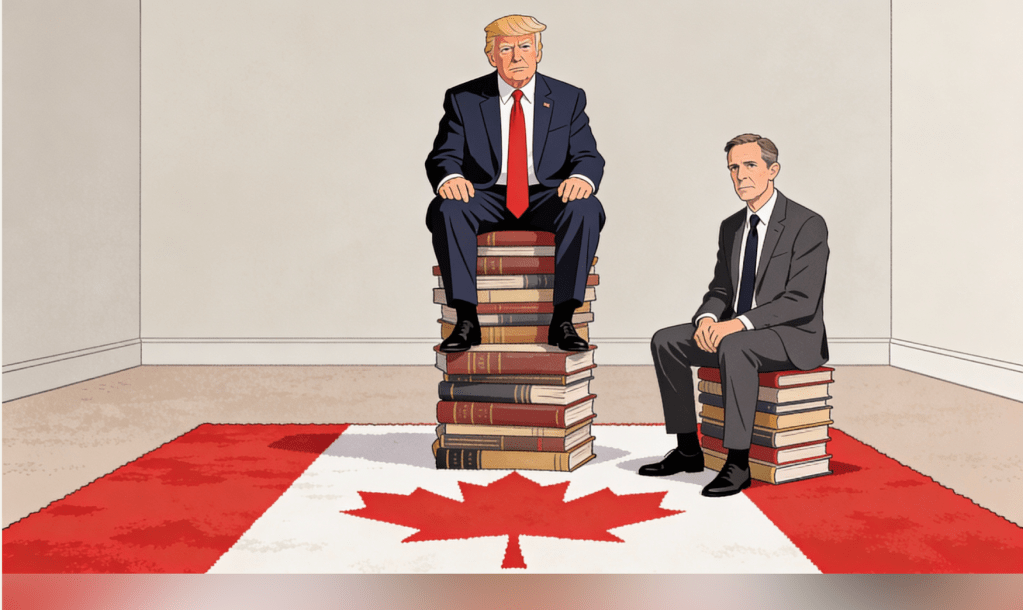

AI illustration by Perplexity

January 24, 2026

Richard Stursberg, Lament for a Literature: The Collapse of Canadian Book Publishing (Sutherland House).

If we ever were, Canadians are no longer happy to be cultural North Americans.

The current US administration’s plan is to reduce Canada to a vassal state, like Russia’s Belarus.

Canadians have responded with fear, anger and pride. We are, the vast majority of us, resolved to defend our cultural sovereignty by any means necessary or available.

Enter stage right, Richard Stursberg’s history and policy statement on Canadian book publishing, Lament for a Literature. It’s more of an essay than a book at 96 pages with no footnotes to slow you down and, somewhat irritatingly, no index. It’s published by Sutherland House, one of the small and feisty Canadian publishing houses that are the objects of the author’s cultural affection.

The melodramatic book title is a riff on George Grant’s 1965 classic Lament for a Nation. Long before Canada bet big on North American integration, Grant meditated upon the death of Canadian sovereignty. He described a withering away of the Canadian identity and questioned our resolve to resist the black-holed gravity of the United States.

Stursberg articulates the essence of the matter in his first paragraph (inviting Kim Mitchell’s great compliment: “damn, I wish I wrote that”):

A country’s identity is forged from its political, military, and social history as interpreted and communicated through its arts. The stories that emerge define how a country thinks about itself, what it values, and how it perceives others. The stories can come in the form of epic poems, TV shows, magazine articles or oral traditions. The Ur medium is books. They provide the most thorough and immersive explorations of identity and often underpin all the other media.

You can pick a bone with any of that if you like, including the claim that books are our cultural supercode, or as Margaret Atwood once described that literary universe, “the geography of our Canadian mind.” (Alas, Atwood’s acerbic wit got the better of her when she playfully designated those uninterested in Canadian books as “cultural morons.”)

Despite long form narrative having to compete for attention with the Internet, we are still a nation of book readers with the time and patience for that immersive wonder.

The trouble is, Stursberg writes, the Canadian book business has largely collapsed over the last 20 years. We have the weakest domestically-owned publishing sector in the industrialized world (a measly five per cent of book revenues in its own market); we prefer celebrity memoirs and self improvement books to Canadian biography and politics; we’re mostly reading American fiction and non fiction distributed by the foreign publishing houses and their Canadian subsidiaries that have the other 95% of sales in the Canadian market; and our tight cohort of prominent Canadian novelists are increasingly setting their narratives outside of Canada, whether out of artistic vision or with an eye on foreign distribution.

For all of this, Stursberg puts the blame on public policy failure, going back decades.

The public policy for supporting the arts and media in our small Canadian market is always a variation on a theme: government subsidies underwrite the cost of Canadian culture so that art which is truly local and authentic will earn enough money that the Canadian media companies making a business of selling and distributing Canadiana can make a go of it.

For books, the largesse is not lavish: the federal funding of the Canada Book Fund ($50M/yr) and the Canada Council book program (another $40M/yr) are rounding errors of a federal budget rounding error.

But the key thing is that unless we’re going to cut subsidy cheques to foreign book publishers (we don’t), we need a regulatory framework that keeps Canadian media companies strong.

The thinking goes, the foreign book houses are in Canada to make money. But their diminutive Canadian-owned counterparts are in it for both the love and the money. However the small scale of the Canadian-owned houses makes them vulnerable to economic rip tides and the occasional financial crisis. That is why regulatory and government support to grow their business scale, and to build a backlist of great titles and a stable of bestselling authors, can be the key for Canadian publishers to survive the day and live to publish more Canadiana.

Stursberg recounts the narrative of how peculiar (and fatal) it was that federal policy on Canadian book publishing failed to follow the more successful regulatory model supporting broadcasting.

Where Pierre Trudeau’s 1968 broadcasting legislation demanded Canadian ownership of all television and radio broadcasting, his corresponding book policy in 1974 grandfathered American publishing houses already here while impeding further foreign takeovers of Canadian publishers.

When Brian Mulroney’s heritage minister Marcel Masse tried to strengthen the takeover rules in his “Baie Comeau” book policy (named for the location of the cabinet retreat where it was approved), he later ran into the headwinds of the Mulroney cabinet’s natural instincts and eagerness to make a free trade deal with Ronald Reagan.

At the first real test of Baie Comeau, Mulroney green lit the Gulf & Western conglomerate’s takeover of the Canadian-owned Prentice Hall. Over the next two decades, under Conservatives and Liberals alike, the Baie Comeau policy supporting small Canadian book publishers was enforced poorly and then not at all. Today it is effectively a dead letter.

Stursberg reminds us of the bestselling and buzzworthy fiction and non-fiction that Canadian owned publishing houses once brought to market: Peter Newman’s Renegade in Power and The Canadian Establishment, Grant’s Lament for a Nation, Pierre Berton’s The National Dream and the Last Spike, Mordecai Richler’s St.Urbain’s Horsemen, Leonard Cohen’s Beautiful Losers, Alice Munro’s Bear, and Atwood’s Surfacing and Survival to name a few; many of them prize winners in Canada and internationally.

Stursberg writes of the tragedy of the Canadian publishing powerhouse McClelland & Stewart, with its dream team backlist of iconic books, falling into financial crisis and, after some serious skullduggery, emerging eleven years later as foreign-owned but not before new owners feasted on $77 million in Canadian subsidies. Plenty of villains in the piece, and not all foreigners.

Today the Canadian subsidiaries of foreign publishing houses can cherry pick the best Canadian authors and books, while the smaller Canadian-owned houses embrace the commercially challenged mission of mapping the geography of the Canadian mind. As for the authors that Canadian publishers bring to success, they can hardly resist the lure of foreign book houses for their next title, what with their global distribution and Canadian marketing budgets.

But Lament is a policy treatise and, like Stursberg’s 2019 manifesto on broadcasting The Tangled Garden, he is not shy about providing an answer to the question “what is to be done?”

His answer is a multi-point program of more generous federal book subsidies and regulatory support for Canadian publishers that he would put in the hands of a Canadian crown corporation. As a kind of CBC for book publishing, federal BookCo would be backed by a tougher policy on Canadian ownership (to protect the last five per cent of our market) and supported by a nationalist policy to grow that five per cent through book distribution and publishing rights, as well as leveraging federal money to persuade provincial governments to imitate Québec’s policies supporting French language authors and books. It’s a bold menu that would see powerful enemies queueing up and US trade negotiators at the front of the line.

As we head into the ugly confrontation with the US in upcoming trade talks, it’s an opportunity for Canadians to stake our claim to cultural sovereignty. Better to fight on our feet than become vassals on our knees.

***

If you would like regular notifications of future posts from MediaPolicy.ca you can follow this site by signing up under the Follow button in the bottom right corner of the home page;

or sign up for a free subscription to MediaPolicy.ca on Substack;

or follow @howardalaw on X or Howard Law on LinkedIn.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME. But be advised they are public once I hit the “approve” button, so mark them private if you don’t want them approved.

I can be reached by e-mail at howard.law@bell.net.

This blog post is copyrighted by Howard Law, all rights reserved. 2026.

2 thoughts on “Of books, sovereignty and morons. A review of Stursberg’s ‘Lament for a Literature’”