The Netflix Plan, c.2015

November 20, 2024

Until Parliament passed the Online Streaming Act in 2023, Canada did not have a Netflix Plan. Instead, Netflix had a Canada plan (note the witty meme, above). You could write a book about it.

Last Friday the CRTC announced a fresh round of hearings to implement the regulatory framework for foreign video streamers and Canadian television broadcasters.

While the Commission previously ordered Netflix and the Californian streamers to pay $140 million in annual contributions to Canadian media funds, this newest regulatory file is the most consequential thing that the CRTC will do for Canadian television and video streaming.

The hearing notice for March 31, 2025 tips the CRTC’s hat in terms of the regulatory changes it wants to make, although it’s not final and is subject to debate. The changes will become law in the summer or fall of 2025 unless interrupted by a federal election campaign (which seems more likely than not).

The “too long, don’t read” summary (and this is a long post) is this:

- The headline is some minor tweaking of the definition of a “Canadian program,” the first step before assigning the foreign streamers a programming budget for Canadian shows.

- A far more important proposal concerns who should own the long term copyright and commercial opportunities for a Canadian program that is made by a Canadian producer and then licensed and distributed by Netflix or the other US streamers.

- A bold and controversial move by the Commission is a proposal to abolish programming minimums for Canadian television drama (“Programs of National Interest” in CRTC-lingo) which have been centrepiece of the Commission’s regulatory remit for decades.

- The Commission wants to do something significant to support television news, presumably through subsidies, but unlike the other issues in its announcement it doesn’t appear to have any idea of how to do it.

What is Canadian?

The argument over what ought to be considered a Canadian program will never stop. It’s like criticism of the CBC: impeaching the cultural status quo is a Canadian parlour game.

We’ve always used the headcount method to define Canadian programs, allocating up to 10 points to a program that stars Canadians and puts Canadians in the key creative jobs of producer, director, writer and a few other talent slots that are deemed to contribute to the look, feel and vibe of a show.

The governing principle is that we can count upon Canadian artists to make Canadian art. Or as the Commission puts it with so little rhetorical flair, “having Canadians responsible for key creative decisions will enhance Canadian stories.”

Netflix and the other streamers aren’t crazy about the headcount test. If they are going to be required by the CRTC to make Canadiana, they want to use their own people. Their people are Hollywood actors, directors, writers and showrunners; the hand picks whom the streamers believe they can count upon to make hit shows with global appeal.

Some Canadians think that instead of the headcount method we should be qualifying programs as Canadian with a “cultural theme” appraisal of the plot, story, location, and —to use the CRTC’s language— cultural signifiers and symbols. The British do it that way in the UK. They use a panel of television executives to vet programs as British enough for subsidies.

In last week’s announcement, the Commission rejected the cultural theme test as too subjective. In a technical briefing provided to the media, Commission spokesperson Scott Shortliffe said that the cultural test was too difficult to administer because of irreconcilable views on “unifying” Canadian symbols and signifiers. (IMO the latter argument is unconvincing: Canadian culture is a mix of national symbols and diverse, locally authentic signifiers. Canadiana does not require classic cultural totems like Vimy Ridge or the Canadian Pacific Railway to call itself Canadian).

In its announcement, the Commission focussed on tweaking the headcount formula in a number of ways, introducing points for “showrunners” of Canadian TV series; giving credit for employment of Canadian costume designers and make-up leads as well as visual and special effects wizards. The Commission also relaxed the rule that all personnel sharing a point-eligible role (for example multiple writers of an episode) have to be Canadian: now one in five can be non-Canadian.

This is all nibbling around the edges of the current point system. In an incremental way it might allow Hollywood streamers to use more Hollywood talent on a Canadian show, but it’s no game changer.

Whose money is it anyway?

When Netflix was asked by Parliamentarians in 2022 what amendment to Bill C-11 it wanted the most, the one-word response was “copyright.” The amendment didn’t fly.

“Copyright” was short-hand for Netflix saying that if the Online Streaming Act compelled foreign streamers to sink millions into distinctly Canadian shows, it expected to own those programs lock, stock and barrel. “Copyright” meant not just the possession of first release in Canada and all global markets, but also ownership for the streamers’ permanent libraries of shows as well as the intellectual property of series spin-offs, branding, merchandise and any other long term commercial opportunities.

Unfortunately the streamers’ expectation that they own a show, rather than license it from Canadians, runs smack into Canadian regulatory rules that favour copyright and intellectual property residing with the independent Canadian television producers who make Canadian dramas and license them to broadcasters home and abroad.

The CRTC backs this up by requiring Canadian broadcasters to spend a fixed tranche of their programming budgets on “Programs of National Interest” (Canadian dramas and documentaries) and buying at least 75% of shows from independent Canadian producers.

Those Canadian producers retain the copyright and intellectual property in those shows because the government and media fund subsidies that finance these Canadian shows are conditional upon the producers retaining the commercial control and exploitation of their shows for 25 years. For producers, it’s seen as the difference between being an entrepreneur and a gig worker on their own shows.

The foreign streamers hate these rules, but they are operating in Canada and they are going to have to get used to them.

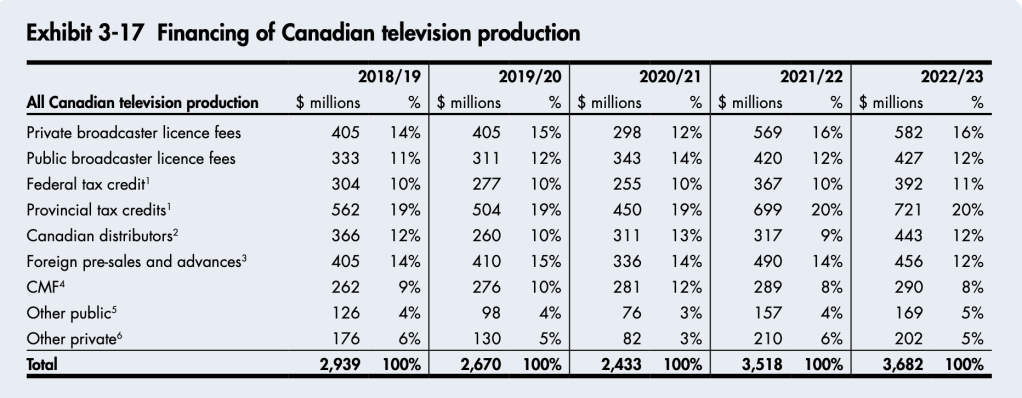

From the Canadian point of view, these are the regulatory rules that allowed us over decades to build a thriving film and television sector across multiple production clusters in Vancouver, Toronto, Montréal and increasingly in other provinces. It’s the reason why the Liberals amended Bill C-11 to make pro-Canadian copyright rules explicit. The amendment wasn’t airtight but reflected the reality that the financing of Canadian shows is a mix of Hollywood money, Canadian investment and public dollars.

But this is the real world and the streamers know they can make trouble for Canada by appealing to US Congress and the White House to take on their fight.

The CRTC is not oblivious to this realpolitik, so it is looking for a compromise solution. In the announcement, it invited proposals on how copyright and intellectual property might be shared between Canadian producers, broadcasters and foreign streamers. While the Commission did not elaborate on how, these sharing models could be targeted to specific genres of shows, markets or the size of their programming budgets. After all, the streamers are potentially bringing the big budgets that Canadian television producers might not otherwise obtain and are expanding access to global audiences beyond the usual foreign partners in cable television distribution.

The Commission also mooted the possibility that Netflix could “buy” outright copyright by maxing out on the use of key Canadian talent, a proposal that might drive a wedge between Canadian producers and Canadian production guilds. The Canadian wing of the set workers’ union IATSE, based in Hollywood, has been explicit about this already.

This is going to be regulatory dog fight, you heard it here first.

Watering down rules on television drama

Canadian television regulation has always given special treatment to financing and promoting Canadian drama since at least 1979, when the CRTC ordered the CanCon-laggard CTV to produce 39 hours of original shows per year.

Because of the market dynamic of a small domestic audience for Canadian content in both Québec and the rest of Canada, television drama is —as the CRTC reminds us in its last announcement— “risky to produce and difficult to monetize.”

A fulsome production and subsidy ecosystem is built around government and industry subsidies plumping up programming budgets for Canadian dramas and documentaries made by independent Canadian television producers. The programs are dubbed with some grandiosity by the CRTC as “programs of national interest (PNI).”

Further regulations require major broadcasters to dedicate a large slice of their programming budgets to the PNI genre (ranging from 5% to 15% of revenues).

Yet another regulation completes the ecosystem by requiring those broadcasters to buy 75% of their PNI-qualifying programs from the aforementioned independent producers (and in practice broadcasters do almost no in-house production of dramas and buy 100% from these producers).

The broadcasters don’t mind buying from the independent producers; they do mind filling a quota of PNI spending. They have been seeking reductions in PNI for years.

They appear to have got their wish.

The Commission is now proposing to eliminate the broadcasters’ PNI programming obligations.

It’s reasoning seems to be:

- The foreign streamers are in the business of television drama, so if they have to make Canadian content there will be more “PNI” dramas without having to specifically require it.

- The Commission’s proposed changes to the definition of Canadian content will encourage the production of dramas (IMO, this is a stretch).

- Canadian broadcasters want to make less risky and more profitable content (the elephant in the room is the debt-laden Corus Entertainment, which has sought to satisfy their CanCon obligations with more reality and lifestyle television and fewer dramas).

- Without a PNI spending quota, the production of Canadian dramas can still be encouraged by giving streamers and broadcasters extra credit for making dramas (i.e. a reduced overall budget for Canadian entertainment content in proportion to spending on drama).

- The Commission should reserve its most stringent regulatory efforts for encouraging news production.

Save the furniture

Canadian broadcasters have a legitimate list of woes. Cable subscriptions are steadily declining. The television advertising market is going out with the digital tide. Access to popular US programming for retailing to Canadian cable customers is getting more expensive and less available.

All of that jeopardizes their ability to produce local news, a money loser for 12 years running.

The Commission’s most recent announcement sends strong signals of its desire to save television news from further erosion.

If the Commission has anything in mind other than homilies about the value of local news, it’s keeping its cards close to the vest. Instead, industry participants have been invited to make proposals.

“Level the Playing Field”

The Commission’s announcement answers some of the questions about how foreign streamers will contribute “equitably,” measured against the efforts of Canadian broadcasters to finance and promote Canadian content.

The Commission has linked its expectations of streamer spending on Canadian programs to the “Canadian Programming Expenditure” (CPE) requirements for major broadcasters, pegged at 30% of Canadian revenues. This CPE is less than it could have been if the streamer obligations had been benchmarked to Canadian “specialty” broadcasters whose “CPE” minimum averages at about 29% of revenues but in practice is 48% of revenues.

The streamers’ CPE will be at least 30%, but probably much less in the end, for these reasons:

- The streamers’ 30% will be reduced, perhaps more than dollar for dollar, by the 5% cash contributions the Commission already ordered streamers to make to Canadian media fund.

- The Commission has already signalled in last week’s announcement that it might reduce overall CPE in proportion to money spent by streamers and broadcasters on making “risky and difficult to monetize” Canadian dramas; and

- The Commission could end up pushing the 30% benchmark lower by granting the pleas of major broadcasters to reduce their CPE to 20% or 25%.

Notably, the Commission has folded the broadcasters’ regulatory relief requests into the file for the upcoming hearings.

Discoverability rediscovered

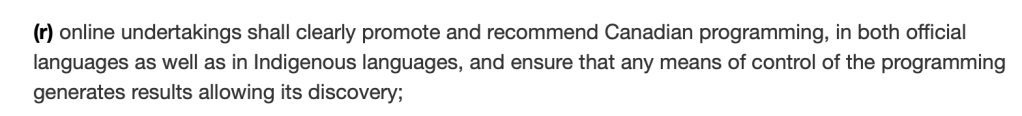

Ever since the Online Streaming Act received Royal Assent in May 2023, the Commission has been squirming in discomfort over how to implement the new statute’s “discoverability” mandate that streamers must recommend Canadian content on their platforms “by any means of control.” The Commission has repeatedly disavowed “regulating algorithms” to achieve discoverability outcomes, overstating the statutory prohibition that the Commission may not prescribe a “specific” algorithmic method.

In a briefing for media on last week’s announcement, the Commission stated that its approach to discoverability would be integrated into each regulatory proceeding rather than scheduling a special hearing on the topic. Its spokesperson made a point of mentioning the importance of discovering French language content on foreign streaming platforms, a hot issue in Québec.

Until we hear a more concrete proposal from the Commission, it may be safe to assume that the lip service to discoverability will continue.

Getting under the election wire

In the media briefing, the Commission suggested it wanted to conclude hearings and issue rulings on the regulatory actions raised in its announcement by summer or fall of 2025. (In case you are wondering, a year ago the federal cabinet allowed this much time by setting December 2025 as the deadline for the Commission to implement the “regulatory framework” for the Online Streaming Act).

However if the writ is dropped for a federal election (likely no later than August 2025) the Commission would observe political custom and put a hold on release of its rulings.

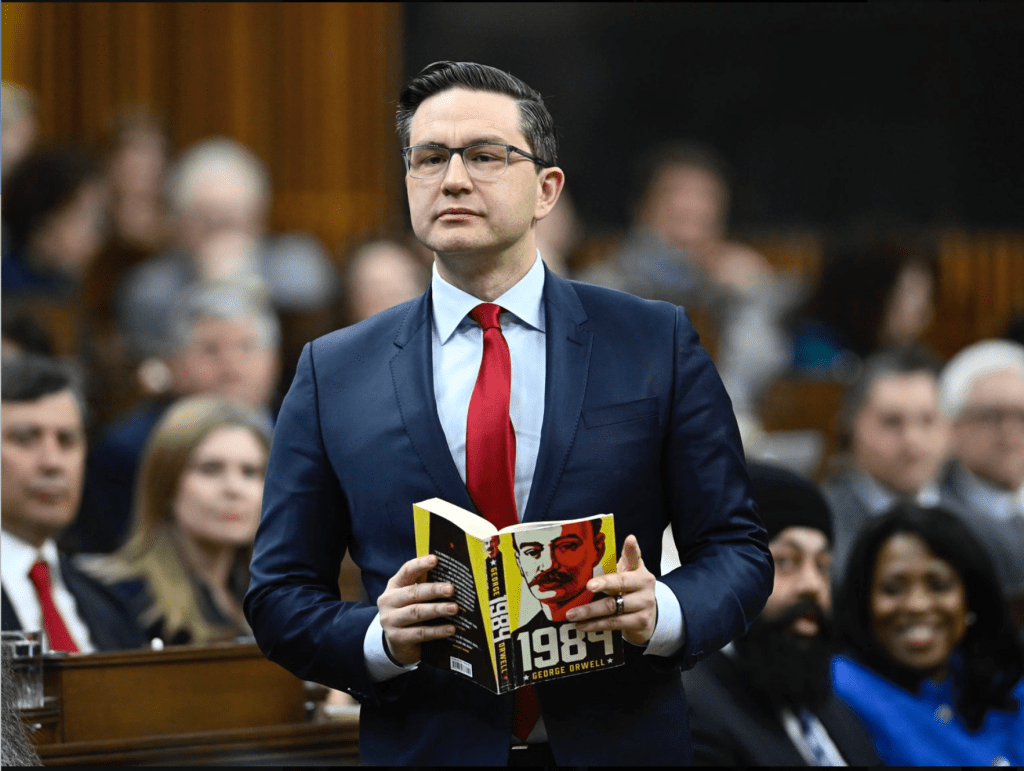

Barring a political miracle, the Poilievre Conservatives will form a majority government before the end of 2025 and they have repeatedly promised to “Kill Bill C-11.”

***

If you would like regular notifications of future posts from MediaPolicy.ca you can follow this site by signing up under the Follow button in the bottom right corner of the home page;

or e-mail howard.law@bell.net to be added to the weekly update;

or follow @howardalaw on X or Howard Law on LinkedIn.

10 thoughts on “The CRTC maps out its Netflix plan”