March 15, 2025

The magic of Donald Trump is that almost anyone invited to his reality show in the Oval Office is automatically his foil and a civilized person: Trudeau, Macron, Zelensky, Starmer and maybe soon Mark Carney, all avatars of the old international rules-based order. Somewhere, somebody is making book on Trump’s soon-to-be-released diss for Canada’s 24th Prime Minister.

Yes, the civility of the old order is long gone. MAGA’s toxic masculinity is about to have a very long run. You avoided these guys in high school, but now they are in your face.

The old order was run by Americans too. Pax Americana in foreign relations. The “Washington consensus” on open markets and the elimination of tariffs. The “new world order,” ironically.

The credo was so dominant (and the US market so inviting) that in 1988 Canada laid all bets on an open trading relationship and an integrated continental economy: something Canadian governments had pursued on and off since Confederation in 1867.

So having played by America’s rules, it’s galling that Trump now wants to use tariff warfare to devastate our economy and take our jobs. Deep down we always knew the US colossus had a taste for conquest. We just didn’t think it would be us.

It’s especially grating when Trump lies to the American public, makes up fake numbers about trade deficits, counts goods but not services, and then insists that deficits are inherently unfair (except where America is in surplus).

Last weekend I posted a video of former Unifor economist Jim Stanford providing context to the US-Canada trading numbers. Here’s the detailed text version.

Stanford makes a number of important observations about size of the cross border trade deficit in goods and services and, as any first-year university student would, reminds us that a trade deficit is not a thermometer of economic health, wealth, or fair play.

“Trump’s claims that Canada is benefiting unfairly from the bilateral relationship, and is in fact subsidized by the U.S., are false,” says Stanford, “and Trump’s economic team certainly knows it.”

The US has run a global trade deficit for fifty years in a row. The gap is now approaching one trillion dollars annually. But as a percentage of American GDP, the US deficit is in modest decline to about three per cent of its economy.

What’s not often cited is the fact that the US is a global juggernaut and net winner in services —digital products, e-commerce, tourism, transportation, financial services and so on—all of which tamps down that trade deficit generated in industries that sell “goods.”

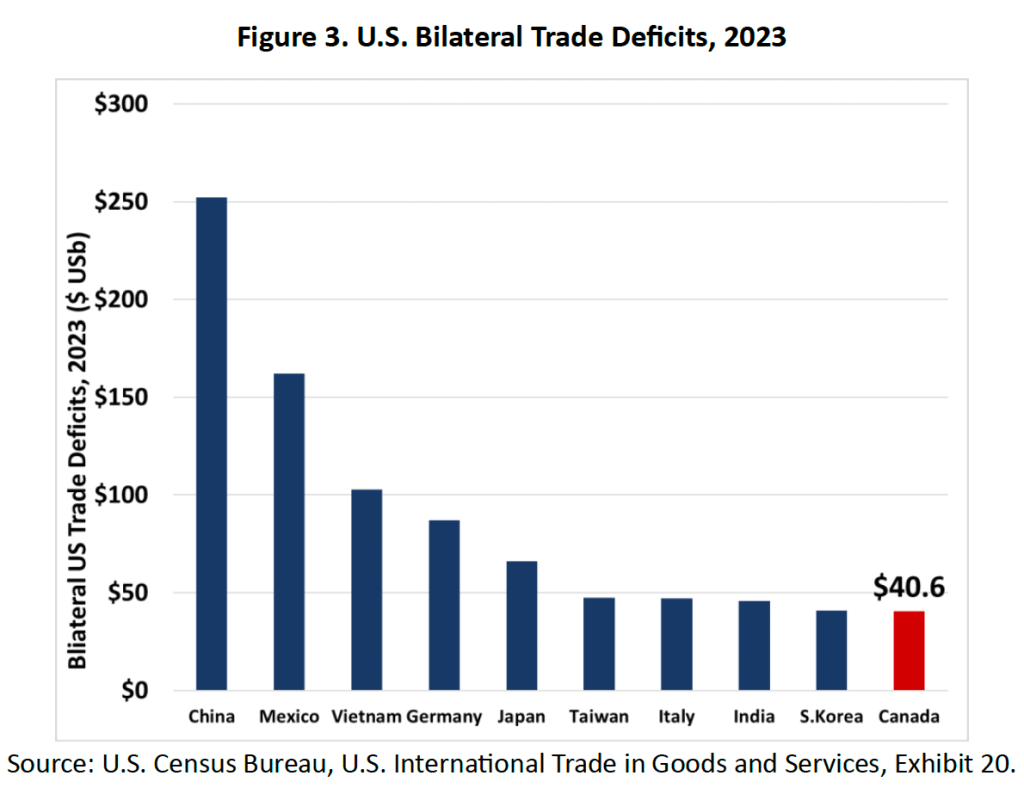

Canada is the US’s biggest export market yet our trade of goods and services is the closest to balanced of any major US trade partner.

The US sells 92 cents of goods and services to Canada for every dollar of goods and services we sell to them.

That trade “imbalance” puts us way ahead of the US benchmark of selling less than 80 cents to the dollar with its major trading partners, with nine of those other trading partners more “out of balance” than Canada.

And the south flowing of trade includes duty-free Canadian oil, gas, electricity and coal. Those vital energy products account for the majority share of the US deficit in goods. It may be that Trump wants to wean the US off of Canadian energy (although it will take years to do so) as if we were the unreliable ally.

In fact most Canadian exports to the US are raw materials and inputs to American products. That’s good for American consumers and good for American exports of finished products (including back to Canada, affirming the half-truth that Canada exports raw materials in exchange for finished products).

But commerce in goods is only half of the trade picture. In services alone, the US has a strong surplus with Canada. For decades, Hollywood boasted of the surplus-building role it plays in exporting cultural services (television shows and movies) to Canada and the world. Its Californian cousins in Big Tech are now doing the same thing in digital services.

In addition to counting services whenever measuring trade, says Stanford, the cross-border repatriation of profits and investment capital made by Canadian and American companies in each other’s markets results in an unofficial trade surplus for the US.

Another unofficial trade number that doesn’t show up in conventional statistics, says Stanford, is that Canada (and the rest of the world) buys more US government bonds than the US buys from Ottawa.

The US is mired in massive government debt but bondholders in Canada and abroad are delighted to snap up its treasury notes. That drives up the US dollar and makes US exports more costly than they might otherwise be.

Remember that when you buy Florida orange juice.

Stanford says that most economists agree that its hard to pin down the value of trade in services —which affects the calculation of trade balance— because of how easily masked that value may be:

One challenge in understanding the impact of services trade is the incomplete and approximate nature of statistics on services trade. It is harder to account for cross-border transaction in services (much of which occurs digitally) than to measure cross-border flows of physical merchandise (which is regulated and logged at border crossings).

Another factor is the ambiguity of intra-corporate accounting for transactions between non-arms-length subsidiaries of international corporations; intra-firm accounting for items like administration costs, intellectual property charges, and profits can be easily manipulated, often motivated by efforts to reduce corporate tax liabilities (by artificially shifting bottom-line profits to subsidiaries located in lower-tax jurisdictions).

Officially, the US export of services to Canada is significant and in surplus to the tune of $32 billion. In fact that US surplus with Canada ——what US Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick would label as “trade dumping” were it the other way around—— is the US’s second biggest service surplus with any of its trading nations.

Oh, and the largest US service surplus is with….hold your breath now….Ireland.

Ireland.

Why is that? One big reason is that Big Tech books a chunk of revenues and profits in its holding companies parked in low-tax Ireland, a country that taxes foreign corporations at half of American and Canadian rates and one-quarter on earnings from intellectual property.

The holding companies technically own the intellectual property for Big Tech conglomerates that pay themselves for their own IP assets to reduce taxes on revenue earned all over the world.

That’s my parsed version of what Stanford has to say.

His prescription will sound similar to things you have already heard from others:

[We] need to include aggressive efforts to expand trade links with other countries; equally aggressive efforts to reorient Canadian production around domestic (rather than export) markets; emergency fiscal measures to support domestic spending power and household financial stability in the wake of industrial disruption and unemployment (potentially funded in part with revenues from export taxes and/or tariffs imposed by Canada in the event of a trade war); and a national strategy to build alternative domestically-focused industries (including affordable housing, sustainable energy, and human and caring services) to fill the void left by a downturn in export industries.

This is a daunting scenario, but not impossible.

***

Over the past four years of posts to MediaPolicy.ca I have written about US-Canada trade relationship in cultural products.

The narrative is always a story of Canadian legislative initiatives and the corresponding US trade threats.

There are three books that are helpful to read if you are interested.

In 2004 Peter Grant and Chris Wood published “Blockbusters and Trade Wars: Popular Culture in a Globalized World.” It’s a superb explainer but begs to be updated. The analysis in Part One (the economics of the global cultural economy) and Part Three (US trade power) still rings true.

In 2019 Richard Stursberg published “The Tangled Garden: A Canadian Cultural Manifesto in the Digital Age.” The third chapter on “The Mulroney Years” is a good read because Stursberg was a senior civil servant and insider in the midst of the US-Canada free trade deal that set the rules in cultural trade for the next generation.

Gary Neil’s 2019 “Canadian Culture in a Globalized World” explains the mechanics of how these trade deals work and impact culture.

Did I say three books? A fourth is my 2024 “Canada vs California: how Ottawa took on Netflix and the streaming giants.” You’ll recognize a lot from the other three books, summarized in Chapter 1.

Also, here are some MediaPolicy posts that cover the thorny US-Canada trade relationship in culture:

325. A “Canada First” trade policy for Canadian culture – January 28, 2025

189. The US Trade Bear, Red in Tooth and Claw – May 26, 2023

***

If you would like regular notifications of future posts from MediaPolicy.ca you can follow this site by signing up under the Follow button in the bottom right corner of the home page;

or sign up for a free subscription to MediaPolicy.ca on Substack;

or follow @howardalaw on X or Howard Law on LinkedIn.

I can be reached by e-mail at howard.law@bell.net.

This blog post is copyrighted by Howard Law, all rights reserved. 2025.

Thank you for explaining the services point, and for referencing the fair play point. I so wish the news contained more of this kind of “reporting”

>

LikeLiked by 1 person