Apple TV’s Canada tab

January 12, 2024

If you’ve read MediaPolicy’s posts over the last three years, you may have noted an affection for opinion polls.

They are hardly a stand-in for policy debate: but public opinion surveys test the mood of the broad populace on any given issue while the political class thrashes it out clause by clause and tweet by tweet. That’s vital in a liberal democracy, no one will dispute.

But poll accuracy has become challenged by one big thing: no one answers the phone anymore. That’s why many pollsters have switched from “random sampling” to “opt-in panels” of poll respondents.

Random sampling is the gold standard, based on pollsters’ outbound telephone calls to about 1500 to 2500 members of the general population, chosen randomly with attention to general demographics. The random selection allows pollsters to afix the label of “accurate within a [ ] margin of error” to assure everyone that the poll is representative of public opinion.

The same “accurate within a margin of error” claim can’t be made for opt-in panels because they aren’t truly random.

The “opt-in” approach is an invitation to participate in a similar sized group of self-selected poll participants. This corps of volunteers can be tweaked by pollsters for demographic balance, but the real challenge is the motivations of the volunteers which can’t always be filtered out by poll questions like “who did you vote for in the last election?”

Plainly put, some volunteer respondents may be gaming the poll questions based on their perception of how the survey results will play in public. Also, it stands to reason that volunteers are more opinionated, more tuned into public policy than the cohort of randomly selected Canadians. “I don’t know” remains an important opinion.

The CBC Ombud Maxime Bertrand opined on this problem after media researcher Barry Kiefl cited a CBC Toronto radio show for relying on an Angus Reid opt-in poll without explaining its limitations. In fact, that pollster publishes a statement on its website to the effect that “if a randomly selected panel of respondents was asked the same questions as our volunteer panel, the margin of error would be ‘x’.” Arguably, that statement is bootstrapping the opt-in method as being more reliably representative of public opinion than it is.

Kiefl also observed that the Angus Reid spokesperson’s appearance on the CBC show was not just limited to reporting results, but added analysis and commentary like a CBC journalist would. Pollsters are not journalists: they run a business and have a stake in convincing the public that their results are accurate.

The Ombud agreed with Kiefl and in the course of his investigation the responsible CBC News manager did too: the limitations of polls should be noted during the newscast and the pollster’s guest appearance should be presented as opinion and not journalism.

***

The CRTC has announced another hearing on the implementation of the Online Streaming Act Bill C-11.

The notice elicited a bit of a yawn from the mainstream press which was more interested in whether a federal election would interrupt CRTC deliberations (the answer appears to be no, but the Commission won’t issue newsworthy decisions during the election period).

This new proceeding will kick off on May 12th and will cover regulatory issues that don’t quite fit into the Commission’s high profile proceedings dealing with cash contributions to media funds, television and video streaming programming for news and entertainment, and the yet to be announced hearing on audio streaming and radio.

The major focus of the May 12th hearing is what the Commission describes as a review of its existing rules governing the competitive rules of engagement between programming and distribution undertakings, with the possibility of extending them online. The regulatory task is to use competition policy to countervail against the market power of big broadcasters and streamers whose gatekeeping poses a barrier to independent programmers gaining exposure for their Canadian content.

Done right, the Commission may open up a real policy discussion on getting the foreign streamers to make the “discoverability” of Canadian content on their Canadian platforms into a reality, instead of a box ticking excercise.

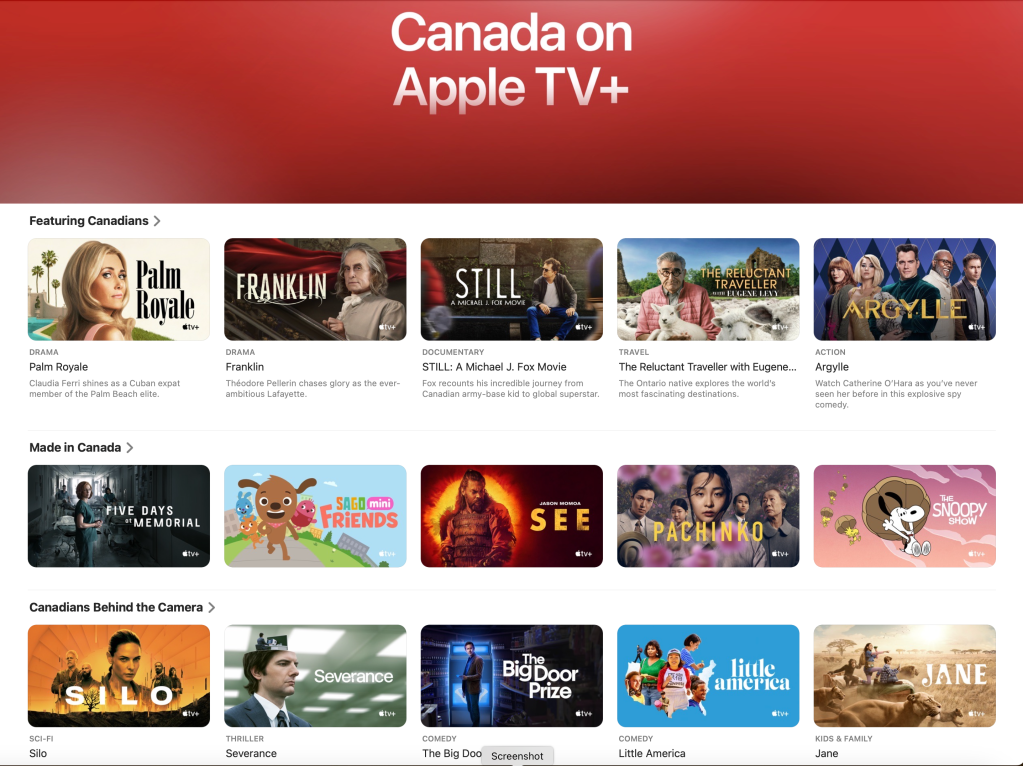

If you look today for Canadian video programming on any major US platform, you will only find it by keyword searching “Canadian” or else locating the “Canadian” page listing a handful of titles, most of which does not come close to being considered Canadian by any reasonable standard. It’s no better on music streaming platforms.

Also —and this surprised me— the Commission will look at the lack of discoverability tools for Canadian content on “smart TVs, mobile handsets, and streaming devices.”

By that, the Commission means hardware that is purchased with the (foreign) manufacturer’s programming apps pre-installed. When I asked the Commission about this a few months ago, I received a one sentence reply “the Commission does not regulate technology.” Now it’s on the table.

Another issue that the Commission is mooting is whether we need new rules to ensure that programming covering “events of national and cultural significance” doesn’t disappear. The Commission has obviously taken note of the rising cost of sports broadcast rights for hockey and the Olympics. It may also be an opportunity to address situations like Rogers forcing the Canadian “One Soccer” channel to crawl across broken glass to get onto cable distribution.

The Commission’s other big focus in this proceeding will be to review existing “access” regulations that support Canadian channels, especially independent broadcasters, getting carried on cable and perhaps have some of those supports extended to online platforms, the new home of program distribution.

The Commission did not give away any preliminary views on what it wants to do. But expect Rogers, Bell and Québecor to show up with demands for regulatory relief and US streamers to make exclamations of incredulity that any of these supports could apply online:

- mandatory carriage of all local stations in a “skinny basic” cable package for $25 per month, per customer

- mandatory carriage of the local Radio Canada and CBC stations

- mandatory carriage of “public service” channels like APTN, The Weather Network, CPAC, OMNI etc. with the compensation rate set by the Commission.

- The 1:1 rule directing Bell, Rogers and Québecor cable operations to include as many independent channels in their offerings as their own.

- customer pick and pay of individual channels

- customer choice of a majority of Canadian channels

While some of these rules are specifically designed for the cable environment, the principle of CBC and independent channels getting their Canadian content carried, and made prominent, on foreign online platforms is what is at stake.

The Commission will also review the existing “Wholesale Code” rules governing, to put it bluntly, the commercial bullying of independent channels and the cable divisions of Rogers, Bell and Québecor favouring their own channels.

***

If you would like regular notifications of future posts from MediaPolicy.ca you can follow this site by signing up under the Follow button in the bottom right corner of the home page;

or sign up for a free subscription to MediaPolicy.ca on Substack;

or follow @howardalaw on X or Howard Law on LinkedIn.

I can be reached by e-mail at howard.law@bell.net.