A Guest MediaPolicy column from Peter S. Grant

January 21, 2026

If you intend to become a student of Canadian broadcasting, the first name you learn is that of Toronto lawyer Peter S. Grant, a son of Kapuskasing, Ontario.

That’s not because he’s the most important figure in Canada’s history of broadcasting, but he may have been the most influential over the last fifty-five years at the CRTC, in private practice, and in public policy. The bio on his website doesn’t really cover it: but his autobiography Changing Channels is like a travel guide of unknown stories, pearls of Canadian telecommunications and media history. His totemic Blockbusters and Trade Wars is still the first book you should read if you want to acquire a deep understanding of Canadian media policy, even though it was published 22 years ago. He was central to the writing of the 2020 Yale Report that provided the blueprint for the Online Streaming Act.

Peter’s the ultimate Canadian cultural nationalist. I’m hearing that’s back in vogue.

Peter’s retired now. He keeps a curated page of legal and policy essays on his website and this timely new piece is the latest addition.

***

Why the Online Streaming Act is Crucial for Canada’s Cultural Sovereignty

by Peter S. Grant

One of Donald Trump’s targets in his war against Canada is the Online Streaming Act. This Act was enacted less than three years ago. And in a recent opinion piece in the Globe and Mail, Peter Menzies has argued that Canada should be prepared to give up the Online Streaming Act in U.S. trade talks to satisfy Trump.

Which raises the obvious question. What does the Act do? Is it important to keep it in place?

What Does the Online Streaming Act Do?

Prior to 2023, online undertakings in Canada were governed by an Exemption Order for Digital Media Broadcasting Undertakings, which had been issued by the CRTC in various forms since 1999. In some versions, internet services were referred to as “New Media”. In 2011, the Commission did a fact-finding inquiry into what were then called “Over-the-Top” programming services. But it concluded in October 2011 that these services had not reached a stage where regulation was required.

However, this all changed with the enactment of the Online Streaming Act on April 27, 2023. That statute amended the existing Broadcasting Act, to implement recommendations of the Broadcasting and Telecommunications Legislative Review Panel. Its report in January 2000 was entitled “Canada’s Communications Future: Time to Act”.

Among its recommendations was for the CRTC to create a registration regime for foreign online undertakings and to ensure that all media content undertakings that benefit from the sector contribute to it in an equitable manner. The Online Streaming Act implemented these recommendations and added section 3(1)(f.1) to the Broadcasting Act, which reads as follows:

Each foreign online undertaking shall make the greatest practicable use of Canadian creative and other human resources, and shall contribute in an equitable manner to strongly support the creation, production and presentation of Canadian programming, taking into account the linguistic duality of the market they serve.

How the CRTC Is Implementing the Online Streaming Act.

The CRTC began the process of implementing the Act on September 29, 2023, when it issued Registration Regulations requiring all online streaming services operating in Canada with $10 million or more in annual broadcasting revenue to register by November 28, 2023.

Then, on June 4, 2024, the CRTC issued Broadcasting Regulatory Policy CRTC 2024-121, announcing a policy to require online streaming services that make $25 million or more in annual contributions revenues and that are not affiliated with a Canadian broadcaster to contribute 5% of those revenues to certain Canadian programming funds. The condition was expected to take effect in the 2024-2025 broadcast year, which began on 1 September 2024, and that this would provide an estimated $200 million per year in new funding for Canadian programming.

The affected foreign streamers promptly appealed this order to the Federal Court of Appeal, arguing on various grounds that the order was not properly made. The matter was heard by the court in June 2025 and we are still awaiting the court’s decision. If the court overturns the CRTC order, the Commission will likely re-issue it in a way that meets the court’s requirements.

Still to come is a CRTC decision requiring online undertakings to make expenditures on Canadian programs as a percentage of their Canadian advertising or subscription revenues. Last fall, the CRTC issued a decision redefining what qualifies as a Canadian program, so this will apply to any Cancon expenditure requirements.

Cultural Sovereignty and Canadian Broadcasting in the Past

Canada has had to deal with foreign intrusion into its broadcasting system in the past. In the early 1970’s, the border U.S. TV stations carried by Canadian cable systems began garnering revenue from Canadian advertisers for their audience in Canada. The same US programs were carried by Canadian TV broadcasters but their ad revenue was undermined by the US stations. The CRTC responded by requiring Canadian cable systems to substitute the Canadian version of the program for the US version. This meant that all the ad revenue from these programs stayed in Canada. Since the CRTC required Canadian TV stations to invest at least 30% of their revenue in Canadian content, this strongly supported cultural sovereignty. Later, the CRTC imposed a requirement on cable systems in Canada to contribute 5% of their subscription revenue to Canadian program funds. So cable systems also contributed directly to support Canadian content.

In the 1980s, Canada negotiated a free trade agreement with the United States. The first version of that agreement was the Canada-US Free Trade Agreement in1989. This was succeeded by the North American Free Trade Agreement or NAFTA in 1994. And this was succeeded by the Canada United States Mexico Agreement (CUSMA) in 2018. CUSMA came into force on July 1, 2020.

In all of these agreements, Canada insisted on an exemption for measures that relate to a cultural industry. The term “cultural industry” includes any person engaged in “the production, distribution, sale, or exhibition of film or video recordings”. Thus it is clear that an internet platforms like Netflix or YouTube would qualify as a cultural industry simply because they distribute film or video recordings.

The existence of the cultural exemption has not deterred the United States from threatening retaliation whenever a Canadian cultural policy adversely affects a US company. Over the last 25 years, the US has complained about a number of Canadian cultural policies, including Canada’s ban on US split run magazines targeting Canada, and the CRTC policy on which US channels can be carried by Canadian broadcast distribution undertakings (BDUs). In all of these matters, however, Canada managed to negotiate a compromise that maintained Canada’s cultural sovereignty.

How Are Online Undertakings Regulated in Europe?

In Europe, online undertakings are subject to the Audiovisual Media Services Directive, which was last revised in 2018. Under the Directive, video-on-demand services like Netflix need to ensure that European content has at least a 30% share in their catalogues and they are required to give prominence to European content in their offers.

The Directive also allows Member States to impose financial contributions on online undertakings to the production and rights acquisition of European works. These can be direct investments or levies payable to a fund. A number of European countries have done so. For example, in France foreign streaming services must invest at least 20-25% of their French revenues into European (primarily French) production. And Italy requires that streaming platforms must invest about 16% of their Italian revenues into European and especially Italian content.

The bottom line is that Europe has recognized the impact of foreign platforms on cultural expression and has taken measures to require them to support European production.

Why Should Canada Focus on Online Undertakings?

There is a simple reason why the CRTC needs to focus on online undertakings. In the last ten years, those undertakings have overtaken the conventional Canadian broadcasting system, eroding cable and TV revenues, and dominating viewing in Canada.

A look at the revenues over time tells the story. The numbers are shown in “Canada’s Network Media Economy: Growth, Concentration and Upheaval, 1984-2023”, published last year by the Global Media & Internet Concentration Project. By 2018, the total revenues from online media services in Canada were about C$14 billion, matching the revenue of the traditional media services. However, by 2023, the revenue for traditional media services had declined to C$12 billion, while online media services revenue had increased to C$27 billion.

In 1997, BDU subscriptions to cable and satellite in Canada were around 77% of households. But by 2025, BDU penetration has declined to only 54% of Canadian households. Corus, the Canadian owner of the Global TV network, is under financial distress.

Who were the beneficiaries? Leading the pack is Netflix, which by 2025 was watched by close to 20 million Canadians. But following behind are Disney+, YouTube, Paramount, Apple TV and Amazon Prime, each of which has millions of Canadian viewers. Yes, there are some Canadian online services like Crave and GEM. But they are dwarfed by the foreign-owned services.

Simply put, the Canadian broadcasting system is now dominated by online undertakings. If Canada wants to maintain any form of cultural sovereignty, it must address the role of these undertakings in its cultural policies.

Are Foreign Online Undertakings Discriminated Against?

US trade officials have publicly said that Canada’s cultural laws “discriminate against U.S. tech and media firms.” A House committee has written urging Canada to suspend what it calls the “discriminatory Online Streaming Act”.

But do CRTC online policies discriminate against foreign firms. As noted earlier, the Broadcasting Act does single out foreign online undertakings and states that they are to “make the greatest practicable use of Canadian creative and other human resources”. But the obligation for Canadian broadcast undertakings is even stronger: “to employ and make maximum use, and in no case less than predominant use, of Canadian creative and other resources in the creation, production and presentation of programming…”

In its initial 2024 decision, the CRTC required foreign online streaming services to contribute 5% of those revenues to certain Canadian programming funds. But was this discriminatory? Not at all. In Broadcast Regulatory Policy CRTC 2016-436, the Commission had already imposed a 5% financial obligation to support Canadian content on all Canadian on-demand services.

So the argument that the foreign online firms are discriminated against is simply wrong.

How Foreign Online Undertakings Can Address Their Cancon Requirements

As we await the CRTC decision on what expenditures on Canadian content will be required of the foreign online services, it may be useful to examine how it might be implemented. If required to make expenditures on Canadian content, an online service would use the required funding to acquire the rights to exhibit the program in Canada. But it could also use the funding to acquire the rights to exhibit the program in other territories, like the US or Europe.

In doing so, the cost of the program to the online service will be much higher, since it would be paying extra to the Canadian producer for the foreign rights. But that higher cost would come out of the global program budget of the online service. By taking this approach, the online service can effectively lower the net impact of the expenditure requirement on its Canadian operation. This approach also has the benefit of exposing Canadian content to a wider global audience.

Canadian producers will be up to the challenge. Canadian programs like Murdoch Mysteries, produced by Shaftesbury Films Inc., are already seen around the world. In fact, Netflix itself has acquired the right to run episodes of Murdoch Mysteries on its Canadian service. And there are dozens of other Canadian producers who have generated popular programs. Foreign online services required to expend money on Canadian content will have many ways to do so.

Conclusion

Given the foregoing, it is clear that keeping the Online Streaming Act in place will be crucial to Canada’s cultural sovereignty. Foreign online services already dominate the broadcasting universe in Canada and must be required to contribute to Canadian audiovisual productions that can speak to Canadians in their own voice. Europe has led the way in imposing local programming requirements on foreign online services. Canada needs to follow suit.

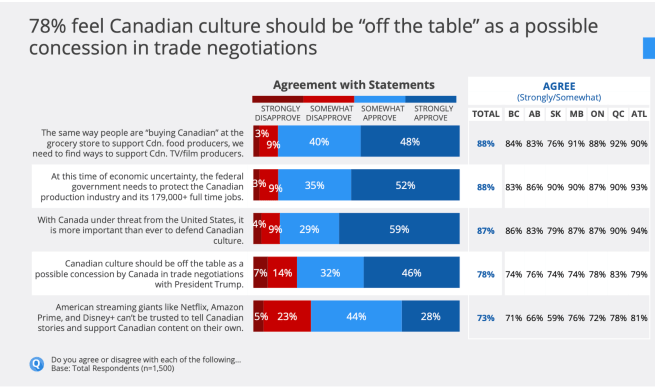

Last September, an online random survey of Canadians was conducted by Pollara, commissioned by the Canadian Media Producers Association. Based on this survey, Pollara concluded that fully 87% of Canadians supported the Online Streaming Act.

This is an incredible level of support, but hardly surprising. In the face of US threats, it is clear that Canadians recognize the importance of cultural sovereignty, including sovereignty over foreign online undertakings.

***

Reprinted by permission

Couldn’t agree with Peter more. This will be the hardest fight for broadcasting sovereignty since NBC told Sir John Aird in the late 1920’s that they would run Canada’s broadcasting system and pay the costs. The Aird Report recommended a national public broadcaster instead, and the CBC was the end result. Will Mark Carney be as steadfast in the face of Trumpian pressure?

Kirwan Cox

LikeLike