Graphic from “Spot Fake News Online,” News Media Canada

January 1, 2025

In the previous MediaPolicy post, we looked at the Pollara/Dais poll of Canadians’ news consumption and trust in news journalism.

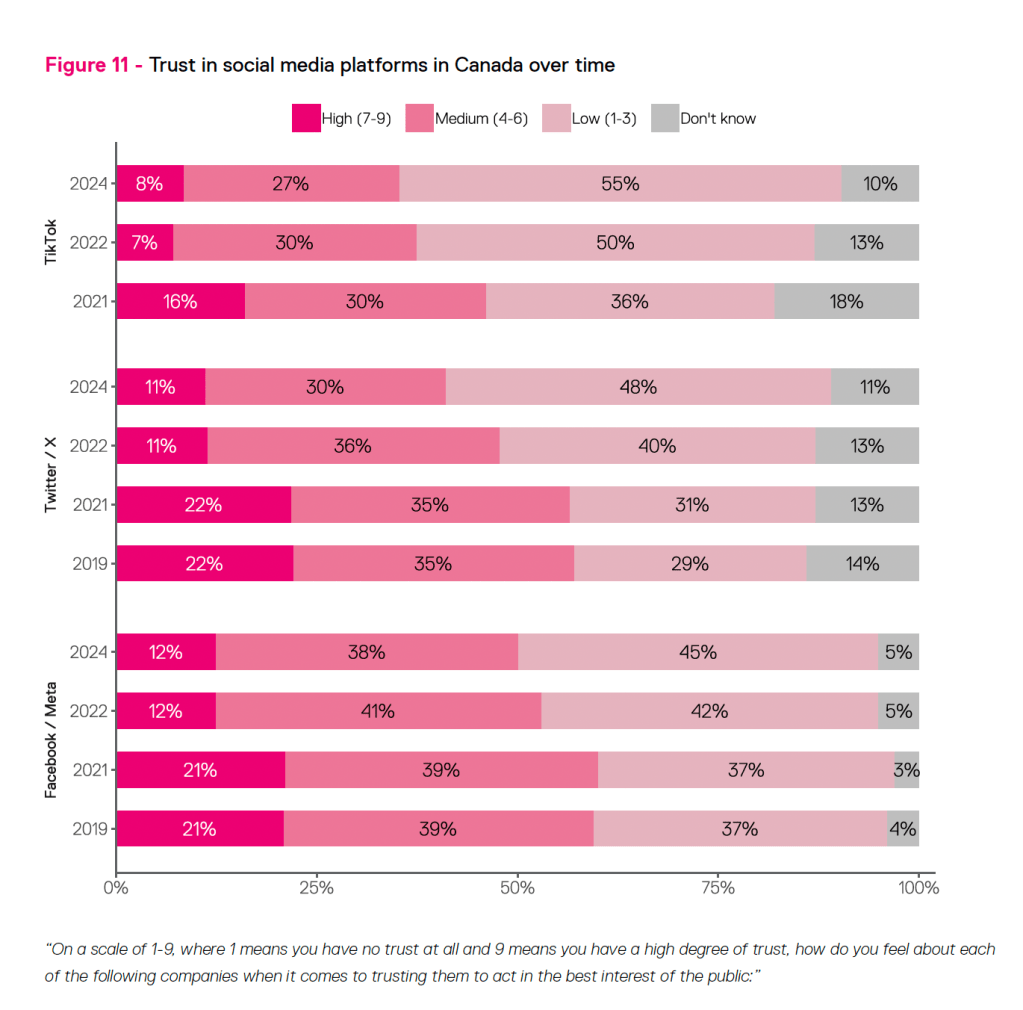

It confirmed what other polls had already established. Overall, Canadians go to mainstream outlets for their news while younger Canadians increasingly get their news on social media platforms such as Instagram, YouTube, Snapchat and TikTok.

Across generations, the lack of trust in content distributed on social media is high.

The other half of the Dais Report (based on the Pollara survey) lasers in on the harms from online misinformation and hate. Just so I don’t bury the lede, the most salacious finding was that right-wing Canadians are far more prone to believe misinformation than left-wingers are. I’ll get to that lower down in this post.

The scope of Dais investigation overlaps but does not quite match the focus of the Liberals’ proposed online harms legislation, Bill C-63 or the Conservatives’ alternative, Bill C-412. Maybe that is because the idea of State intervention to combat harms to children, deep fakes, and revenge porn are uncontroversial. It’s the debate over hate and misinformation that heats controversy.

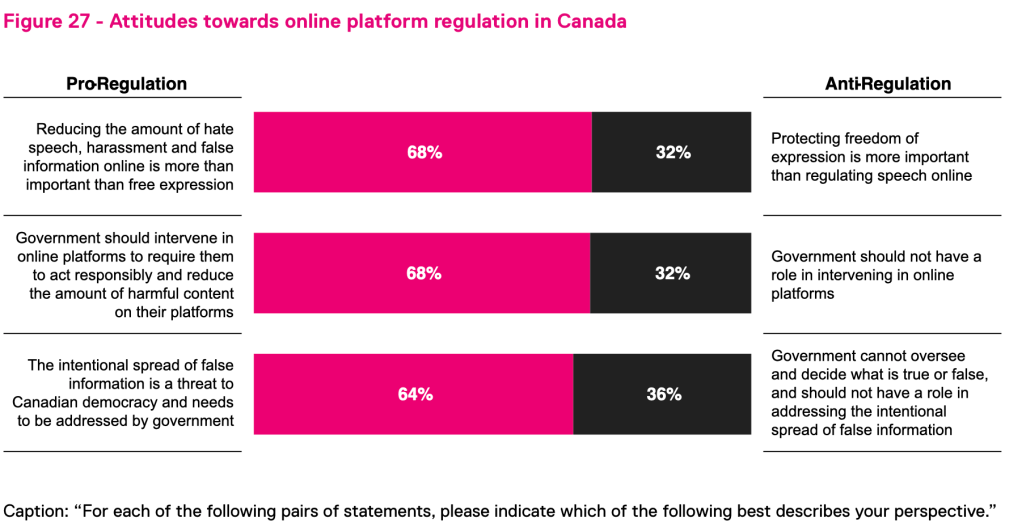

Majority support for fighting online harms

The Dais report looks at public attitudes towards the State stepping in to the ring to regulate online misinformation and hate. The bottom line: two out of three Canadians say fighting online harms trumps the freedom to misinform or hate:

An even stronger majority in favour of State action gets teased out of the poll numbers when differentiating between specific harms and consolidating “strongly” and “somewhat” support:

This polled majority support for State action against online harms is consistent with results in three previous polls.

Is public sentiment an endorsement of the Liberal bill? There is only a modest level of public awareness of the specifics of Bill C-63. Only nine per cent of Canadians think they know details of the bill and another 28% are “vaguely” aware. This is typical of public attitudes towards proposed legislation so the Dais/Pollara survey has to be taken as a snapshot of uncrystallized public opinion on the bill. As well, there has been no poll testing whether combatting online harms is a vote-changer in the upcoming election, as there was with the Conservative proposal to defund the CBC.

Nevertheless a take away from all this polling suggests that the public criticism of Bill C-63 is out of step with public opinion.

the hate you see

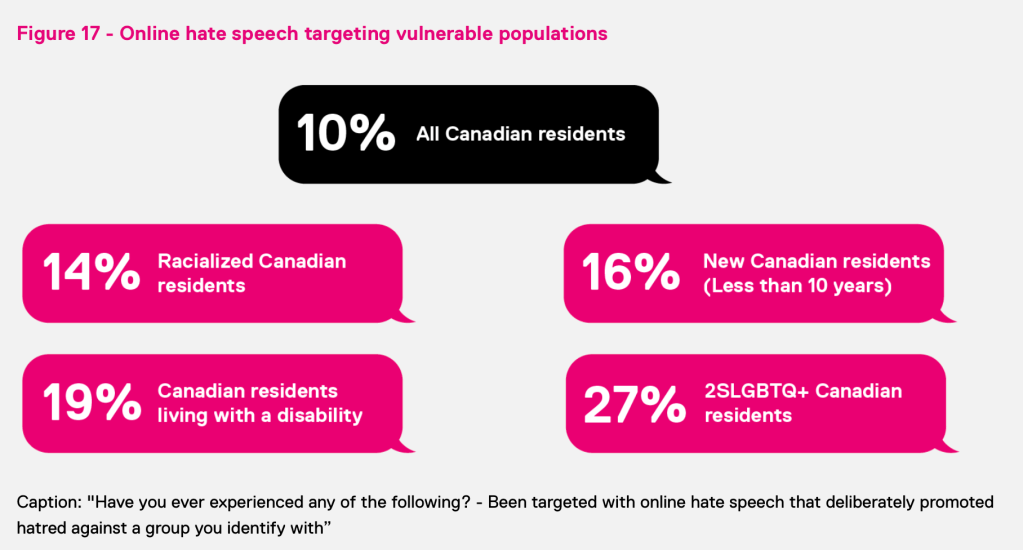

The Dais poll asked survey respondents to self-identify and then, based on the results, concluded that Canadians are seeing a troubling amount of online “hate.” Check out the third line of this graphic:

As for personal targeting, members of racialized and LGBTQ communities experience more of it:

An omission in the survey, which Dais would best be able to explain, is the experience of women being targeted by misogyny and Jews by antisemitism.

Of course hate may be in the eye of the survey respondent and not all hate is illegal. How bad does hate have to be before we censor or punish it?

The legislative standard for illegal hate was written by our Supreme Court adjudicating the Criminal Code and human rights legislation. The legal “hallmarks of hate” are those that vilify and dehumanize members of certain communities, inciting violent and non-violent attacks upon them.

Here’s the Court describing illegally hateful messages:

The messages conveyed the idea that Black and Aboriginal people were so loathsome that white Canadians could not and should not associate with them. Some of the messages associated members of the targeted groups with waste, sub-human life forms and depravity. By denying the humanity of the targeted group members, the messages created the conditions for contempt to flourish.

Moreover, the level of vitriol, vulgarity and incendiary language contributed to the Tribunal’s finding that the messages in the case were likely to expose members of the targeted groups to hatred or contempt. The tone created by such language and messages was one of profound disdain and disregard for the worth of the members of the targeted groups. The trivialization and celebration in the postings of past tragedy that afflicted the targeted groups created a climate of derision and contempt that made it likely that members of the targeted groups would be exposed to these emotions. Some of the posted messages invited readers to communicate their negative experiences with Aboriginal people. The goal was to persuade readers to take action. Although the author did not specify what was meant by taking action, the posting suggested that it might not be peaceful. The Tribunal found that the impugned messages regarding Aboriginal Canadians and Jewish people attempted to generate feelings of outrage at the idea of being robbed and duped by a sinister group of people.

While incitement to violence is a powerful justification for censorship of hate, the common understanding of incitement as direct cause and effect may not capture hate’s long term poisoning of the mind: Jews are too rich (so take away their property); Indigenous are idle (so don’t hire them); Blacks are violent (so keep them in a ghetto).

The incitement to violence is just a further matter of accumulating a critical mass of dehumanization. The bereaved Afzaals of London Ontario probably would like to know how many haters and hate messages it took to incite the man who murdered their family with a pick-up truck.

It’s really not surprising that Canadians’ majority support for action against online hate is so high. Whether or not expanding the existing anti-hate legislation that is already on the books through C-63 is the answer, there are many informed discussions to consider. And it’s important to keep in mind that much of the bill doesn’t deal with hate speech.

taking the misinformation quiz

The Dais report also puts a lot of focus on misinformation. Neither the Liberal nor Conservative bills propose to regulate misinformation, other than where it’s present in harm to children, deep fakes, and hate speech.

It’s not well known that Canadian television and radio regulations have long prohibited “false or misleading news” in broadcasting. I can find no cases where the CRTC took action on those grounds (although a there have been censures and licence revocations for the “abusive comment” of misogyny and racism over the airwaves).

When Parliament updated the Broadcasting Act in Bill C-11 in 2022 it excluded regulation of “abusive comment” and “false or misleading news” from applying to content distributed on social media platforms such as YouTube. The federal cabinet went even further by excluding podcasts, keeping them unregulated.

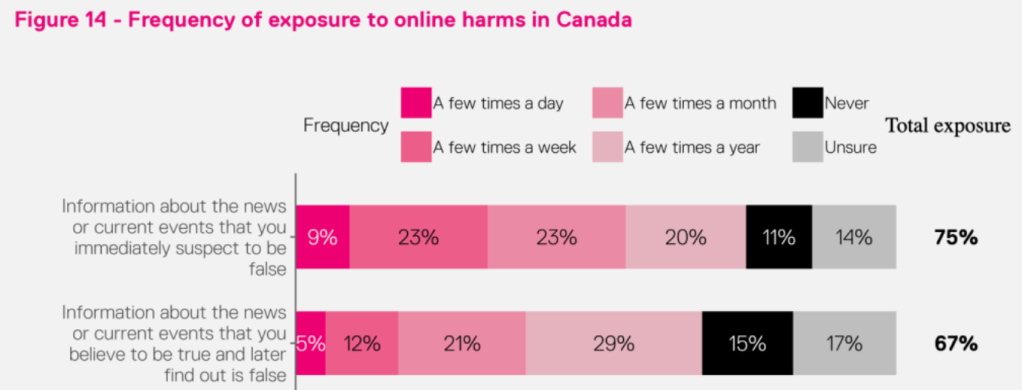

Nevertheless, the Dais Report looks at the size of the online misinformation problem in Canada. This is where I promised the salacious stuff.

First, the polling confirms that Canadians see a lot of “fake news”:

Next, Dais looked at who is especially vulnerable to misinformation, or credulous of it, depending upon self-identified political views of the respondents; right, centre or left wing.

The pollster posed eight true/false questions about current affairs, described below with the correct answers (7 are false, one is true), in order to assign respondents to membership in “low, medium or high misinformation groups.”

Membership in the “low” misinformation group required at least six correct answers out of eight. Respondents were allowed to qualify their answers as “somewhat” true or false, or respond “don’t know.”

Seventy-eight per cent of left-wing identifying respondents scored six or better. Thirty-two per cent aced the test.

Across town in right-wing territory, only 34% scored six or better. Only six per cent nailed all eight.

Men and women performed about the same overall. Older Canadians did dramatically better than the younger generation (62% versus 45% for six or better). University-educated Canadians topped high school and college graduates. And finally, Québec respondents outperformed the rest of Canada by a considerable margin:

If you aren’t wound up enough by this point, consider that left-wing, university-educated, boomers from Québec have to be feeling pretty good about themselves.

Happy New Year.

***

If you would like regular notifications of future posts from MediaPolicy.ca you can follow this site by signing up under the Follow button in the bottom right corner of the home page;

or sign up for a free subscription to MediaPolicy.ca on Substack;

or follow @howardalaw on X or Howard Law on LinkedIn.

I can be reached by e-mail at howard.law@bell.net.