August 20, 2025

The Canadian Press reported last week that the US State Department has an opinion on Canada’s respect for the independence of the press and freedom of expression. And it isn’t good. In fact, we got the MAGA raspberry.

The US produces “country reports” every year to satisfy US Congress that its foreign aid is going to the right place or, in our case, that we’re a suitable trading partner.

Some context first: the Report is a compliance document for Congress. It was not written for us. If the Report’s allegations against Canada happen to line up with Congressional trade complaints against the Online Streaming Act and the Online News Act, that’s part of the compliance.

Trade irritants or not, the Report picks up the vocabulary of Canadian opponents of public broadcasting, federal aid to journalism and any manner of mandatory payments to support Canadian news journalism such as the Broadcasting Act and the Online News Act. It’s “discriminatory,” it’s “censorship.”

The State Department’s special contribution to the debate is it’s view that our federal government’s $10 million enrichment of existing Canadian media funds to support news reporting in minority communities smacks of “DEI” and discriminates against white journalists.

Not that we needed the State Department to remind us, but the Report goes on to list incidents that occurred in 2024 which, in Washington’s opinion, raise “significant human rights issues including credible reports of serious restrictions on freedom of expression and media freedom, including unjustified arrests or prosecutions of journalists and activists.”

The Report gets one right, off the top, by reminding us that in January 2024 the RCMP arrested Indigenous journalist Brandi Morin when she refused to leave the federal police force’s inflated “media exclusion zone” at an Indigenous protest she was covering for Ricochet Media. What the Americans might have added was that this is hardly the RCMP’s first offence on media exclusion zones. The Crown withdrew the charges and the RCMP’s Civilian Review committee took Morin’s side and an apology was issued.

Another incident cited may or may not clear the bar of a “credible” report of press freedoms violated, that will be up to a judge if lawsuits proceed.

The State Department takes at face value the allegations raised by Rebel News against a venue landlord and a Liberal MP that Rebel was wrongly arm-twisted into paying $37,000 in security costs for a MAGA-themed rally it organized in Toronto, headlined by the US President’s son.

Canada doesn’t do country reports on American freedoms. It’s probably just as well. But the United Nations does. All UN signatories to the Convention of Human Rights participate in a five-year “peer review” of each other that includes press freedoms.

Here are a few items that might come up:

During street protests against the immigration-related arrests in Los Angeles in June, an LAPD officer deliberately aimed and shot an on-camera news journalist with a rubber bullet, hitting her in the foot.

The Federal Communications Commission initiated an investigation of Media Matters, a left-leaning critic of right-wing media, Elon Musk’s X platform and the Republican Party. A federal judge issued an injunction against the investigation on the grounds of 1st amendment rights of free speech.

By President Trump’s executive order, the US government defunded and put almost all 1,300 reporters working for the Voice of America on leave. His appointee to run the VOA, Kari Lake, accused the VOA of a liberal bias and mooted putting the news organization under the direct control of the State Department. VOA is the official US government news agency mandated to communicate government messaging to foreign nations.

US Congress withdrew all federal funding from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, accounting for 15% of the overall financing of NPR and PBS. House Republican Marjorie Taylor Greene stated that Congress was acting because of alleged liberal bias.

While running for President, Donald Trump proposed that the FCC pull the broadcasting licenses of CNN, NBC, ABC and CBS because of their news coverage of him (although the FCC only licenses local stations, not cable news).

The President also sued CBS, alleging that a 60 Minutes interview with Democratic presidential candidate Kamala Harris had been edited and sanitized to her advantage.

The Trump lawsuit resulted in a $16 million settlement without any admission of wrongdoing from the network.

However credible news reports suggested that the FCC might have struck down the $8 billion sale of CBS-parent Paramount to Skydance were it not for a last-minute agreement between Paramount and the FCC that the new owners would scrutinize the CBS newsroom for “multiple viewpoints” and abolish all DEI hiring and personnel policies. According to the President, Paramount committed to providing him with $20 million in free advertising and public service announcements although that was refuted by Skydance.

***

As noted above, the State Department Report repeatedly criticizes the Online News Act and the Canadian Press story on the Report states that “Prime Minister Mark Carney indicated last week he is open to repealing the legislation.”

It’s contentious to report that the Prime Minister said he was open to repealing Bill C-18, although its not surprising that Canadian Press (and the National Post) are surmising it to be true, given his one-eighty on the Digital Services Tax in late June.

The CP and Post descriptions of Carney’s thoughts on repeal are based on a question and answer session with Kelowna Now.

Here is the reporter’s question:

“Bill C-18 stands in our [publication’s] way to get back onto Facebook and Instagram, are the Liberals looking at an alternative or rescinding that so that we can get that news [about wildfires] back on those platforms?

And here is Carney’s answer:

I’ll say this Steve thank you for the question. First thing and one of the things that we have done —and I will answer your specific question, but let me make a point on something we have done, and you may not like this part of the answer but I am going to give it to you— which is that one of the roles of CBC-Radio Canada is to provide unbiased, local, immediate information particularly in regards in situations such as you are referring to. And that’s why we made the commitment to invest and reinforce and actually change the governance of CBC-Radio Canada to ensure that they are providing those essential services.

Now to your specific question. Personally, this government is a big believer in the value of what you do. I’m going to use you as the representation in local news. And the importance for ensuring that that is disseminated as widely and as quickly as possible. So we will look for avenues to do that and I understand your question and it’s part of our thinking around that, thank you.

If we parse closely, the important nuance here is that Carney said he is “looking for avenues to do that and it’s part of our thinking around that.”

Grammatically, the “that” refers both to disseminating local news (especially in light of his comments about CBC-Radio Canada) and “in response to the question” which refers to “rescinding” and/or “alternatives” (or “avenues”). It’s hard to tell what he meant or whether he intended the ambiguity.

If Trump puts enough pressure on Carney, would the Prime Minister cave like he did on the DST ? Unlike the unimplemented DST, the $100 million in Google money is the bird in hand, not in the bush. The mandatory news licensing payments are already in the bank accounts of over a hundred Canadian online news outlets.

Keep in mind, the last time the Liberals came under pressure on implementing the Online News Act was in 2023 when Meta implemented and Google threatened Canadians with a ban on news content, resulting in an approximate $135 million shortfall in anticipated news licensing payments from Google and Meta.

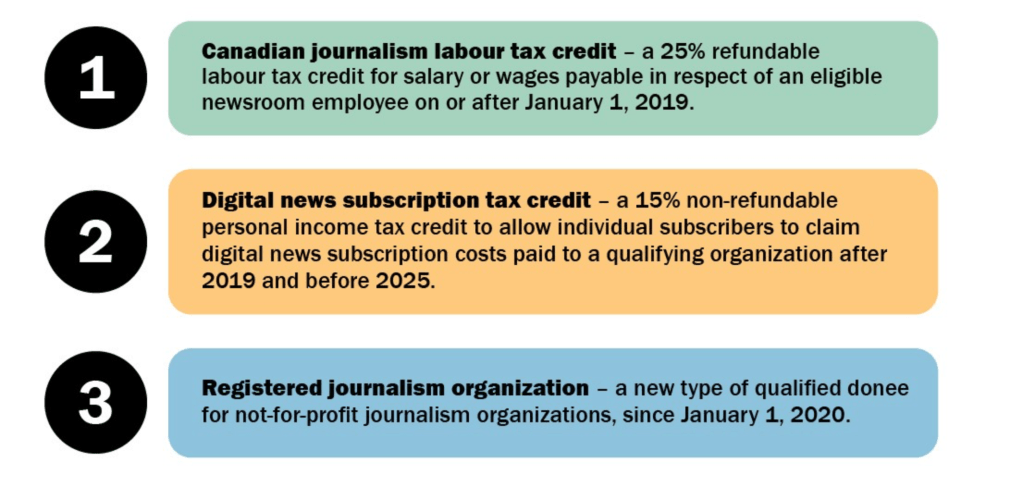

At the time, the government softened the blow of disappointed expectations by increasing the federal QCJO journalist salary subsidies by $30 million.

***

I have a long article to recommend: a New York Times feature that tells the story of Donald Trump’s lawsuit against Paramount’s CBS, the FCC’s approval of the Paramount-Skydance merger and the cancellation of Stephen Colbert’s The Late Show on CBS.

The reporting is based on embargoed access to Paramount owner Sheri Redstone. It’s sympathy for Redstone is not subtle, but it’s an informing read anyway.

***

If you would like regular notifications of future posts from MediaPolicy.ca you can follow this site by signing up under the Follow button in the bottom right corner of the home page; or sign up for a free subscription to MediaPolicy.ca on Substack; or follow @howardalaw on X or Howard Law on LinkedIn.

I can be reached by e-mail at howard.law@bell.net.

This blog post is copyrighted by Howard Law, all rights reserved. 2025.