September 20, 2025

The CRTC is shaping the regulatory path for streaming services in Canada in three big files: audio content, video content and media distribution. The public hearings for video and distribution were done before the summer break and this week the Commission kicked off hearings on music streaming and radio.

The Commission has to figure out what more the global streaming services must do for Canadian content, a year after the CRTC levied on the streamers a “5 per cent” cash contribution to Canadian media funds that match those paid by Canadian cable TV providers.

In music streaming, that could mean new requirements for streamer spending on Canadian songs and musicians through a combination of copyright payments and investments in musician development. It could also mean “prominence” requirements giving an extra push of Canadian songs to the attention of listeners, something that the streamers normally do only if music labels pay them.

Quite significantly, the Commission has already said —-before public hearings kicked off— that it won’t mimic its radio regulations for minimum airtime for Canadian songs. That means the most direct way to address the low consumption of Canadian songs on streaming platforms is already off the table.

The pro-CanCon advocacy group Friends of Canadian Media (I’m a volunteer) says the regulatory algebra should be straightforward.

The streamers’ spending requirements ought to be benchmarked at the same level of radio broadcasters’ budgeted spending on Canadian music and local programming, about 30% of revenues according to the Ontario Association of Broadcasters.

With the benchmark set, next would come the detailed arguments about what streamer expenditures on Canadian music count towards the 30%. The streamers will point to their current budget for copyright payments to Canadian musicians whose songs are uploaded to their platforms, but those don’t come anywhere near filling up a 30% bucket.

Then the “discoverability” requirements would get assessed and Friends has proposed that the Commission require the streamers to promote Canadian music with home-screen prominence, e-mailed song recommendations, more song picking of Canadian music in staff-curated playlists and an algorithmic responsiveness to listeners’ Search inquiries for different types of music. The cash value of these prominence measures to Canadian music producers would be calculated and set off against the streamers’ spending obligations.

The streamers are looking for two things and they want both.

They want the repeal of the five per cent cash levy that supports touring and special development projects for Canadian musicians under the stewardship of independent Canadian media funds. The streamers don’t want to pay and have appealed the levy to the courts.

Also they have filled the ears of the Trump administration and US Congress on how unfairly Canada is treating them (Canadian radio broadcasters pay only a one-half per cent cash levy because they already carry the heavy airtime quotas.)

The other thing the streamers want is no Canadian regulation. Or to put that in regulatory vocabulary, they want whatever efforts they care to make to support Canadian music deemed sufficient. It’s worth recalling that Canada is the first country to regulate streaming audio, even the Europeans haven’t done it yet.

This audio hearing is also the opportunity for Canadian radio broadcasters to bang away at air-time quotas for Canadian songs. As well, they want to water down the “MAPL” definition of what counts as Canadian music for the purpose of meeting those quotas.

The dispute about MAPL —which provides a point system for counting song contributions from performers and songwriters—- will drive some headlines if only because Canadian rock star Bryan Adams publicly trashs it. At some point, MediaPolicy will chime in (again) on that topic.

***

It is hard to keep up with dizzying pace of the Trump administration’s rolling offensive against mainstream media outlets (excepting Fox News of course).

The FCC Chair’s threats of regulatory action against Disney/ABC and the television stations that carried the Jimmy Kimmel comedy show were successful in getting Disney to kill the show after Kimmel lampooned the President’s response to a question about the assassination of his friend and ally, Charlie Kirk.

A day later, the President said that he expected NBC to fire two more late night comedians, Seth Meyers and Jimmy Fallon. He also promised more FCC regulatory action against television networks if they don’t put more conservative guests on air.

As well, this week Trump filed a $15 billion libel lawsuit against the New York Times. A district judge punted the statement of claim as too long and rhetorical, giving Trump’s lawyers a month to refile.

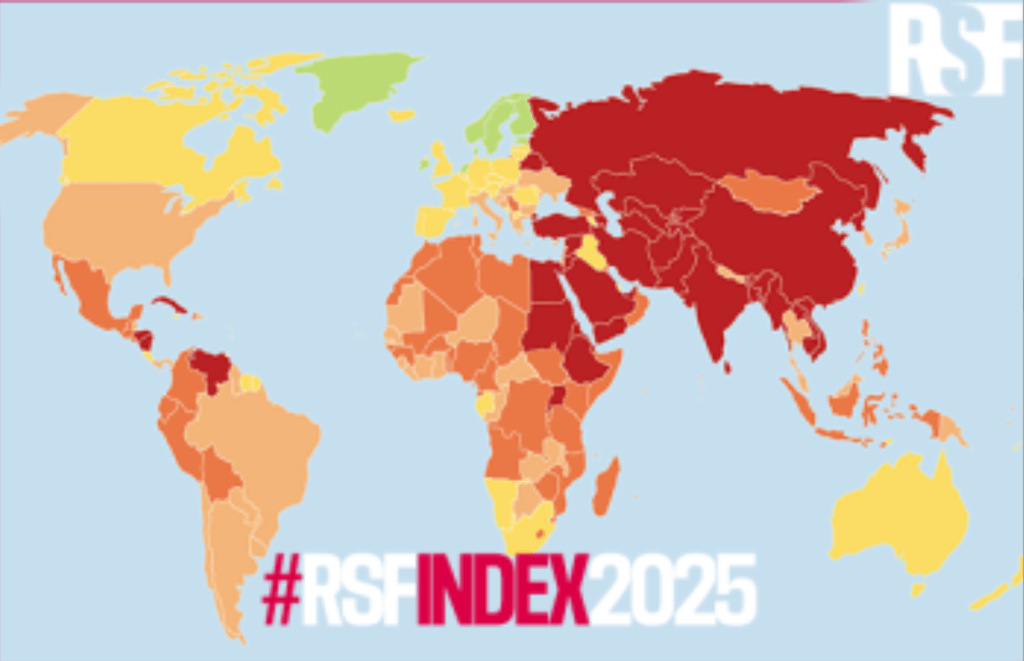

Stepping back from the daily drama, I recommend Matt Stoller’s most recent Substack that sees recent developments as the consequence of successive Republican and Democrat administrations allowing rampant corporate consolidation of telecommunications and media over the last four decades.

Stoller argues that repression of free expression was made possible by a consolidated media landscape, compounded by monopolies in Big Tech.

He has a lengthy list of recommendations, combining anti-trust break-ups of major tech and media companies with new regulatory action that favours more diverse ownership of media.

The ambition of his wish list is considerable, perhaps unrealistic, but it looks to be a campaign proposal to the Democratic Party based on the idea the people are ready to break up Big Media into smaller and more lovable independent media outlets.

***

Lest this blog space seem to be picking on the Americans, I draw your attention to MediaPolicy’s last post spotlighting an on-air anti-Semitic rant from Radio-Canada‘s Washington correspondent.

Élisa Serret described Jewish influence in American politics as “a big machine” fuelled by Jewish money and claimed that “the Jews run Hollywood” and (a new one) that Jews are the mayors of America’s “big cities.”

There’s also a good opinion piece from the Globe and Mail‘s Tony Keller that you might like.

***

If you would like regular notifications of future posts from MediaPolicy.ca you can follow this site by signing up under the Follow button in the bottom right corner of the home page;

or sign up for a free subscription to MediaPolicy.ca on Substack;

or follow @howardalaw on X or Howard Law on LinkedIn.

I can be reached by e-mail at howard.law@bell.net.

This blog post is copyrighted by Howard Law, all rights reserved. 2025.