February 8, 2026

The European Commission has fired a shot across the bow of TikTok, and by implication other social media, by finding the social media giant culpable of addictive algorithm design and inadequate safety measures.

The Commission explained its preliminary ruling, which TikTok can either appeal or fix, as follows:

TikTok seems to fail to implement reasonable, proportionate and effective measures to mitigate risks stemming from its addictive design.

For example, the current measures on TikTok, particularly the screentime management tools and parental control tools, do not seem to effectively reduce the risks stemming from TikTok’s addictive design. The time management tools do not seem to be effective in enabling users to reduce and control their use of TikTok because they are easy to dismiss and introduce limited friction. Similarly, parental controls may not be effective because they require additional time and skills from parents to introduce the controls.

At this stage, the Commission considers that TikTok needs to change the basic design of its service. For instance, by disabling key addictive features such as ‘infinite scroll’ over time, implementing effective ‘screen time breaks’, including during the night, and adapting its recommender system.

The EU finding is made against the Chinese-owned app in the European market, not the American-owned TikTok across the Atlantic. But it will heat up the tension between the US and the EU over the regulation of online harms impacting US-owned apps operating in Europe.

The momentum of regulatory intervention around the globe picked up more steam when Spain indicated its intention to follow Australia and France in banning underage social media accounts.

As for Canada, Heritage Minister Marc Miller isn’t saying yet if a ban on underage access is part of the online harms bill he is preparing.

Last Monday, the influential Taylor Owen and his McGill colleague Helen Hayes called for a moratorium on underage access to social media while online harms legislation gets tabled, works its way through Parliament, and gets implemented.

Judging from Canada’s last two pieces of media legislation, the Online Streaming Act and the Online News Act, the length of the entire process might be measured in years.

What might advance the timetable at the front end is Senate Bill S-209 that would require age verification for porn sites and possibly any social media site that permits porn. The bill passed committee last week and will likely get approved by the full Senate in the next few weeks, putting the governing Liberals on the spot.

Last week Senatrice Julie Miville-Dechêne, the bill’s sponsor, obtained committee approval for a series of technical amendments as well as a change that defined porn more narrowly to get at “X-rated” content and scope out the nudity and implied sexual activity common in mainstream drama. The new definition requires the exhibition of explicit sexual activity and exposed genitalia for the purpose of sexual excitement.

As drafted, S-209 still leaves the decision on whether to scope in porn-permissive social media apps to the federal government, either in a House vote on the bill or afterwards.

***

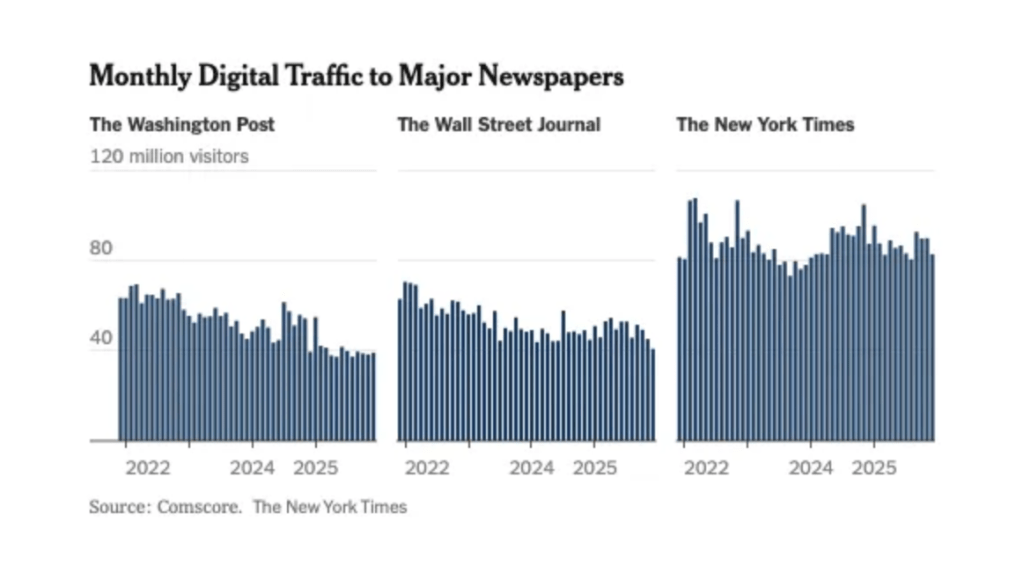

Last weekend MediaPolicy noted the diverging fortunes of the New York Times and the Washington Post with the Times getting the Trump-bump in digital views and the Post sagging in the other direction.

Then on Tuesday the Washington Post announced a breathtaking round of newsroom layoffs, 300 of 800 staff. By Saturday, publisher Will Lewis had resigned.

The public reaction was what you might expect: a mix of shock and anger. Former Post Editor-in-Chief Marty Baron posted his condemnation of the layoffs and put at least part of the blame on multi-billionaire proprietor Jeff Bezos’ decision to ingratiate himself to Donald Trump. That included Bezos killing a planned editorial board endorsement of Kamala Harris’ presidential candidacy, which reputedly cost the Post 200,000 subscriptions, as well as vocal support for Trump’s demolition of the White House east wing and making a donation to the ballroom project to be built on its foundations. Recently, Bezos’ Amazon Prime reputedly overpaid the Trump family for the streaming rights to the documentary Melania.

Then American anti-monopoly advocate Matt Stoller published a long Substack post where he suggested that Bezos bought the Post in 2013 as political insurance against the Obama administration taking anti-trust action against his Amazon e-commerce business. The insurance policy, Stoller suggested, has become unnecessary or overpriced as Bezos literally put his money on Trump.

One piece of context is that while the Post’s declining audience numbers may be attributable to anti-Trump readers voting with their feet, the conservative and pro-Trump Wall Street Journal is experiencing the same decline, although not as steep as the Post.

There were also layoffs in Canadian journalism, suitably smaller in number. Bell Media CTV laid off 60, including 11 television journalists.

***

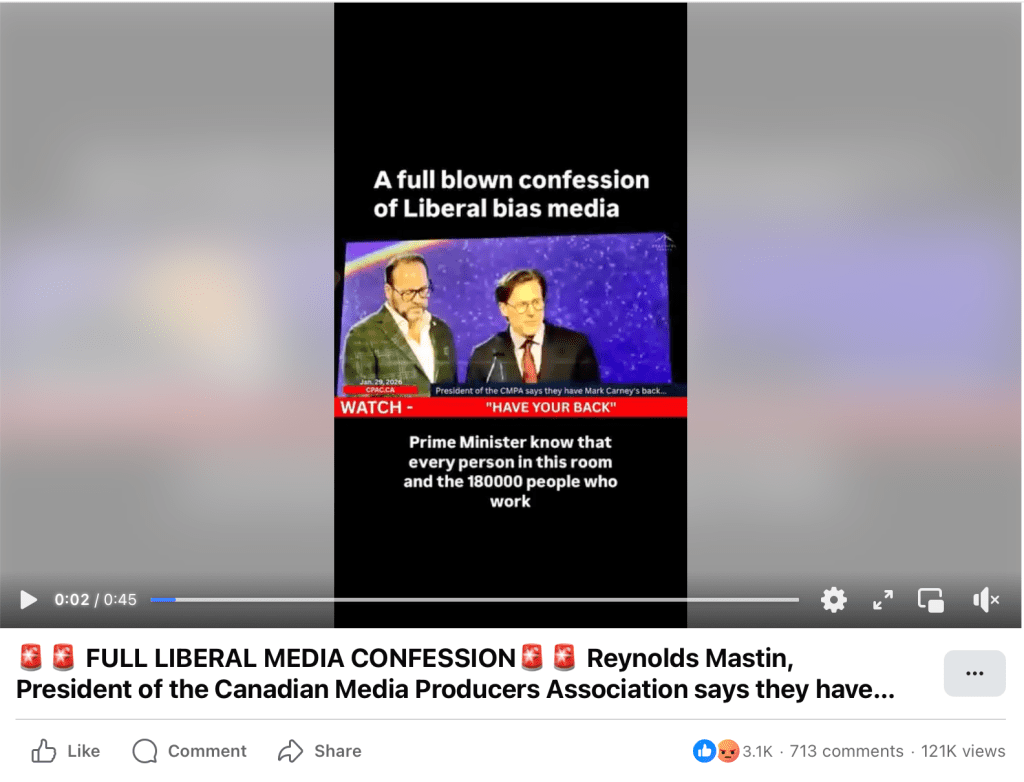

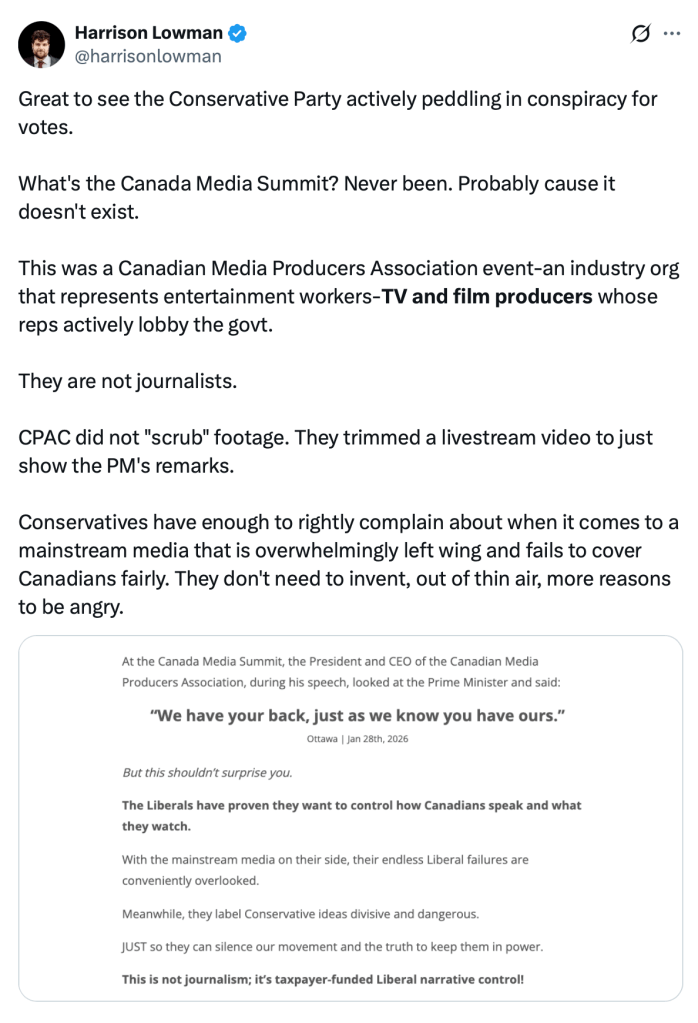

The gong show otherwise known as the right-wing frenzy over mainstream media went viral last week when a video clip surfaced of Reynolds Mastin publicly thanking Prime Minister Mark Carney for “having our backs” and gushing that “we have your back too.”

There it was, proof of the blood pact between the federal Liberal Party and the mainstream news media.

But who the heck is Reynolds Mastin?

Mastin is the President of the Canadian Media Producers Association (CMPA), the industry group representing independent Canadian production companies that make entertainment programming. He was chairing the CMPA’s annual Prime Time conference in Ottawa when he made the remarks.

Readers may know, Mastin is not a journalist and he (and the CMPA) has nothing to do with news journalism. He was encouraging Carney to resist American trade pressure on the Online Streaming Act which requires US streamers to contribute to the Canada Media Fund.

Independent movie and television producers draw CanCon subsidies from the Canada Media Fund to make dramas and comedies. The CMF doesn’t spend a dime on news, although some make the mistake of thinking it does.

Nevertheless, the timing was was perfect for frenzy: the Conservative Party was in the midst of its annual convention in Calgary.

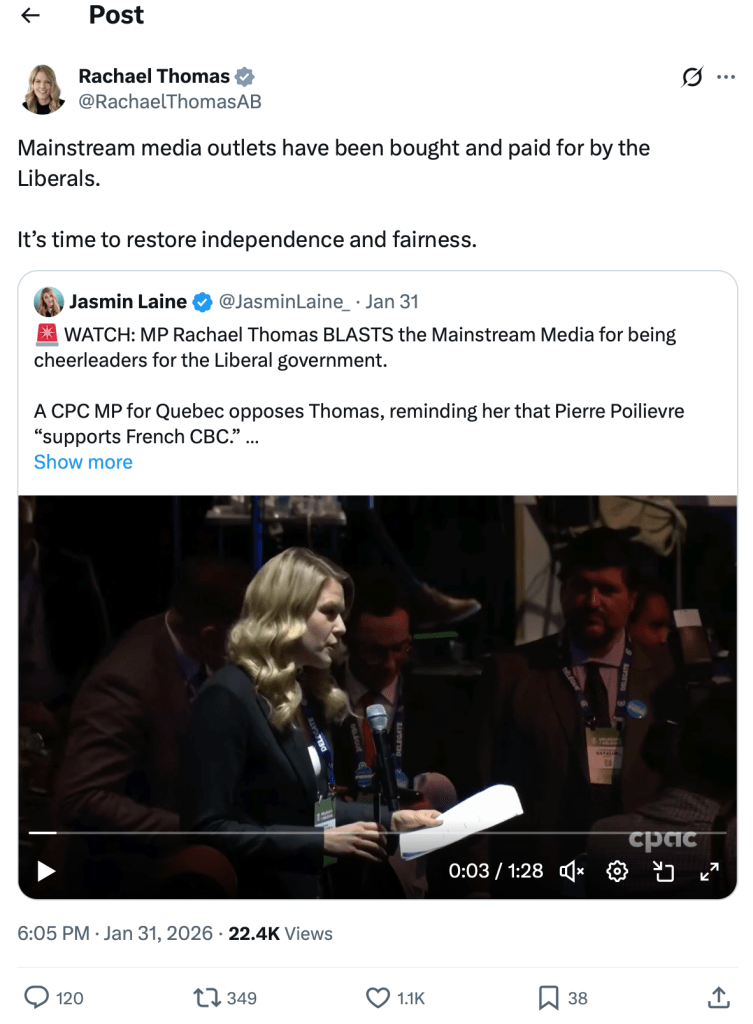

Here is Conservative Heritage critic Rachael Thomas MP describing “the Canadian media summit” as a news journalism event:

Thomas’ falsehoods then found their way into Conservative fund raising e-mails.

At that point, some conservative pundits urged Conservatives to do a fact check. The managing editor of The Hub, Harrison Lowman, was as brave as he was blunt:

Now speaking of Mr. Lowman and The Hub, I can recommend an excellent podcast he did in January with ex-New York Times editorial page editor James Bennet.

In June 2020, Bennet (whose brother is a Democratic Senator) cleared for publication an opinion column from Republican Senator Tom Cotton arguing that Donald Trump ought to deploy the military if necessary to deal with rioting and looting that flared in the aftermath of the police murder of George Floyd.

Bennet’s employment did not survive the newsroom uprising that followed.

A similar newsroom conflagration occurred the same month at Canada’s National Post when columnist Rex Murphy opined that Canada “is not a racist country.”

In any event, I found myself gripped by the full 35 minutes of Lowman’s interview of Bennet and you may find it worth the time as well.

***

If you would like regular notifications of future posts from MediaPolicy.ca you can follow this site by signing up under the Follow button in the bottom right corner of the home page;

or sign up for a free subscription to MediaPolicy.ca on Substack;

or follow @howardalaw on X or Howard Law on LinkedIn.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME. But be advised they are public once I hit the “approve” button, so mark them private if you don’t want them approved.

I can be reached by e-mail at howard.law@bell.net.

This blog post is copyrighted by Howard Law, all rights reserved. 2026.