“G-S-P !

G-S-P !

G-S-P !”

December 31, 2025

You already knew it: Canada’s 2026 is going be a battle, a pivotal moment in our history.

CUSMA talks begin this spring. They will be brutal. Even in the innocent days of cross border free trade, the US played rough when it came to a trade dispute over Canadian culture.

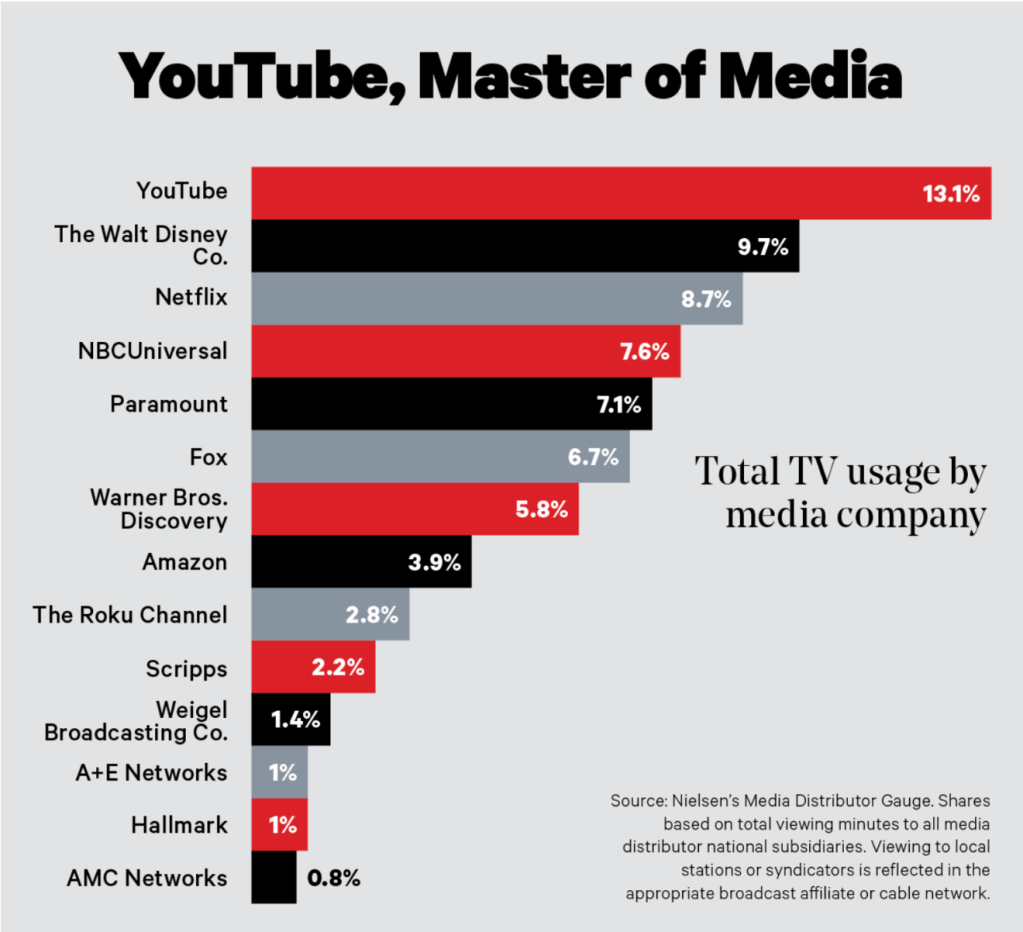

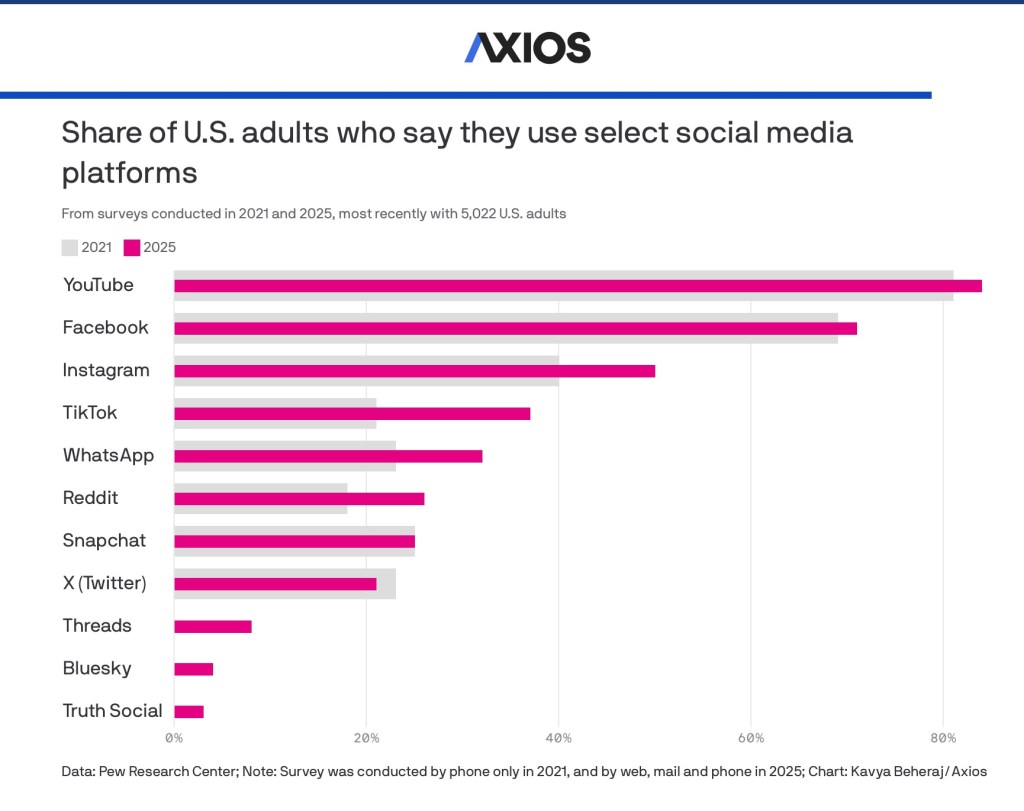

This US President wants high tariff walls to keep Canadian goods out of America and to grab Canadian jobs. Going the other way he wants open borders and unregulated markets for US exports such as streaming services and social media apps.

Given the thousands of Canadian manufacturing jobs and family farms at stake in the trade talks, and the inevitable reprise of 51st state threats —-“we just have to have Greenland Canada”— it may seem parochial at first to focus on media policy. But with 660,000 jobs in our media and cultural sectors, focus I shall.

Here are some of the upcoming headlines.

The CUSMA trade talks

An internet meme recently popped up in my X feed that put two contemporaneous statements from Google spokespersons next to each other.

In the first, Google addressed the digital regulators of a foreign government —-in this case the European Union—- with the utmost respect. In the second statement to a much different forum, Google demanded US Congress stomp all over the EU.

This is how the tech bros roll. They’ve enlisted the Trump administration in their cause and the tiff with the EU has escalated from White House accusations of European censorship of American content to barring the architect of the EU Digital Services Act and four advocates of the EU regulating online hate and disinformation from travelling in the US.

Canada, you’re warned.

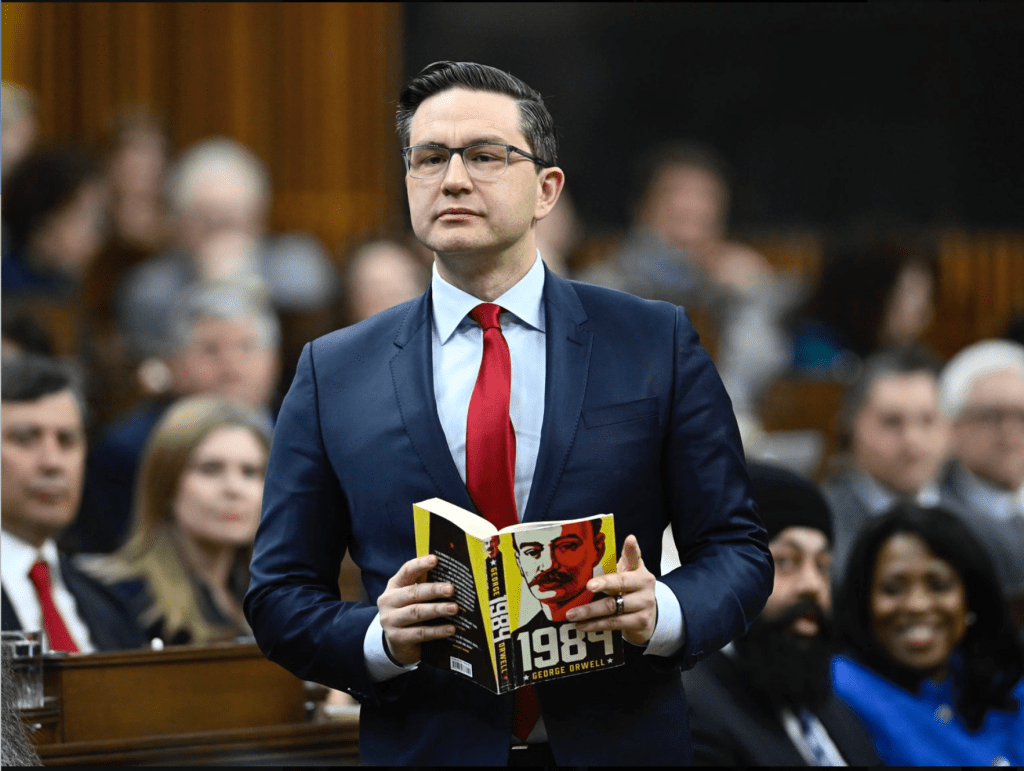

So no surprise, when CUSMA talks begin the US is going to come loud and hard against Canada regulating media in our own country, whether it’s the Online Streaming Act C-11 or the Online News Act C-18. I don’t have a high degree of confidence that PM Mark Carney won’t flush them like he did the carbon tax, the digital services tax, the emissions cap, etc.

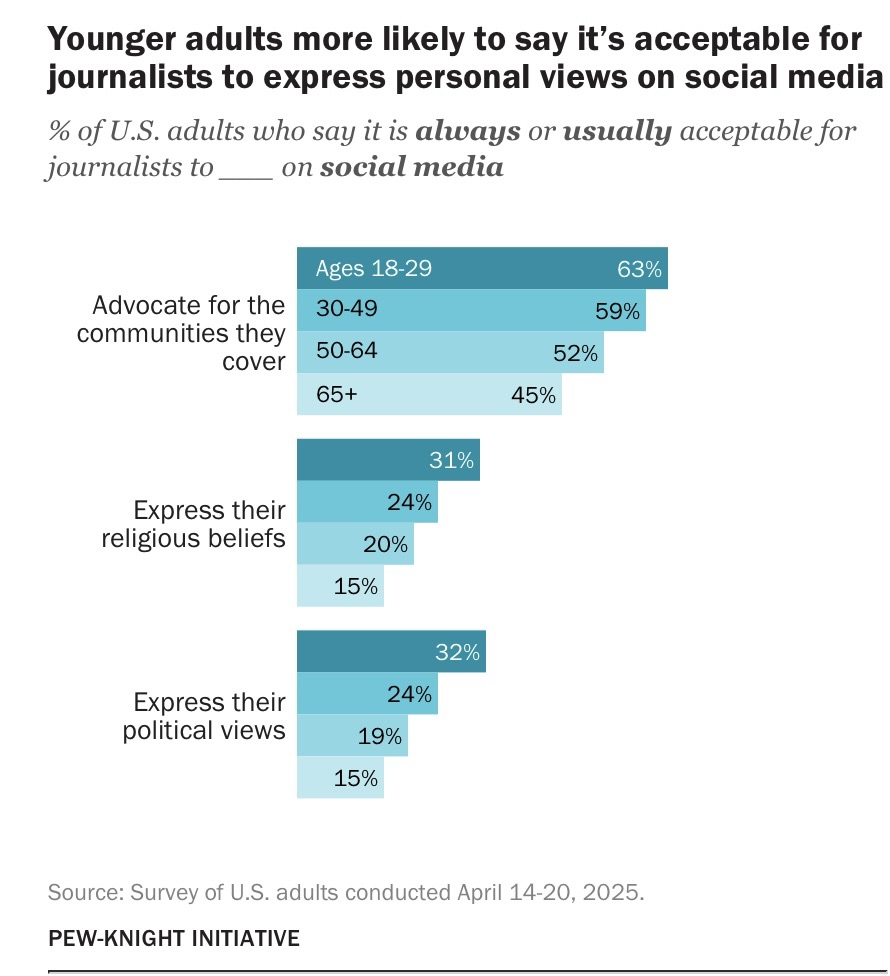

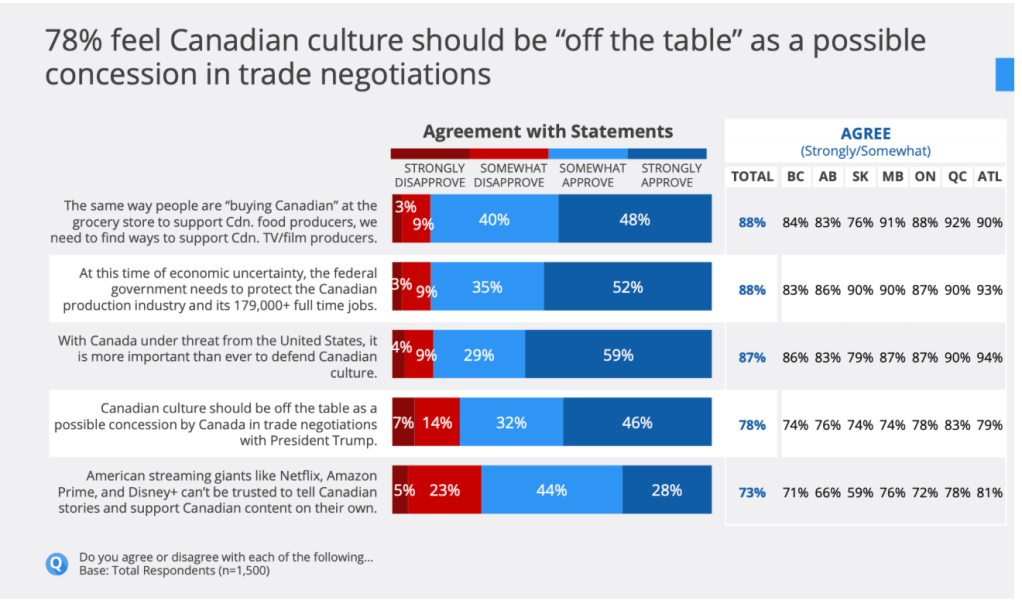

It’s not that we shouldn’t reconsider Canadian media policy any time we want, but it would be better to do so because Canadians wish it. The polls say we don’t: at least not during the trade talks.

What’s at stake here is not only those two pieces of legislation, C-11 and C-18, but our right to take future action on any media policy that might cost the tech bros money or convenience. Think AI. Or online harms.

I make no prediction. On the one hand, as a banker and a corporate lifer I think Carney would happily throw cultural regulation under the bus.

On the other, if he does that he can kiss his Québec caucus goodbye. Or, the NDP might find its gag-point and bring down the Liberal minority government.

CanCon

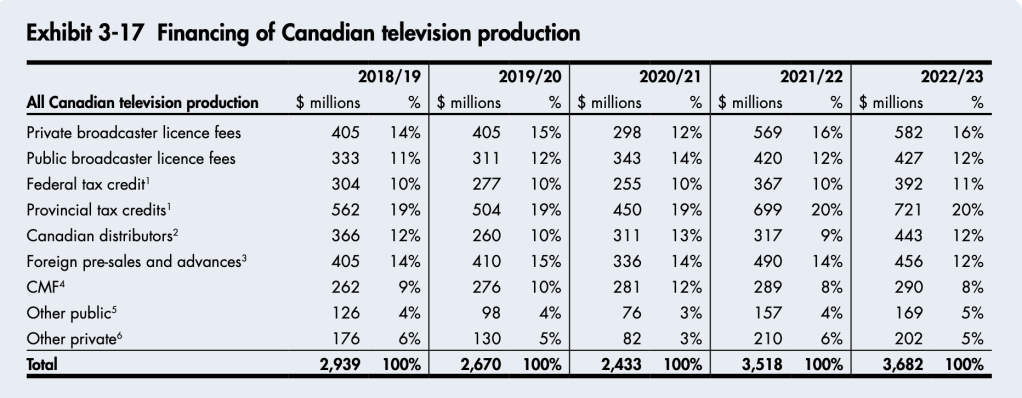

I just can’t figure out the CRTC. The commissioners alternate between putting a bold $200 million cash levy on streaming services and, on the other hand, their timorous ruling on CanCon video content.

The Commission has three big decisions to release in the new year, arising out of the Online Streaming Act (having missed the December 2025 deadline set by cabinet).

The most consequential is the second instalment of the aforementioned CanCon video streaming ruling which will deal with issues that could carve out regulatory conditions for a generation:

- How much money will Netflix and the California streamers have to spend on Canadian shows?

- Will the Commission reduce CanCon spending for Canadian broadcasters (it will) and by how much?

- Will the Commission swap out obligations for Canadian broadcasters to make CanCon dramas in favour of underwriting their unprofitable news operations?

The Commission owes us two other big ones in broadcasting distribution and audio streaming. There are lots of issues packed into those two rulings, but the one I am watching is whether the Commission will make Spotify and the music streamers grow the Canadian listening audience for Canadian artists (it’s currently less than 10%).

There are some wild cards in play.

The Federal Court heard the streamers’ appeal against the $200 million levy in June and judgment is overdue.

The legalities of appeal are narrow and amount to whether the Commission dotted the i’s and crossed the t’s. They don’t allow the streamers to easily challenge the CRTC’s wisdom on the size of the levies, nor what they are spent on (i.e. CanCon dramas and broadcast news).

Still, if the Court strikes down the levies on technical grounds just before the CUSMA talks begin it will significantly assist American negotiators or, if our Prime Minister’s climb down on the digital services tax is any guide, assist him in dumping trade ballast.

Another wild card is Québec’s new streaming law, Bill 109. It’s the CAQ’s claim to regulate streamers in case the federal CRTC disappoints on French language content on screens and AirPods.

When CUSMA talks begin, Québec’s bill will be sited in the same American crosshairs as the federal C-11. With a Parti Québécois election victory in the offing, and possibly another referendum on separation we could hear a lot more about this provincial law.

Next, we can speculate on whether Global TV News makes it to 2027 in one piece. Its parent company Corus refinanced its debt this year and managed to land some new television programming to replace the profitable Disney and Discovery content that Rogers poached from them.

But Corus still lives hand to mouth, and the news division loses a lot of money. The Shaw family ownership can’t find a Canadian buyer. Even Mark Carney wouldn’t dare exempt the 15-city Global News network from Canadian ownership rules and watch Fox or one of the other US television chains march in and set up shop in every major Canadian city.

The last question mark is a boutique policy issue but carries huge consequences for the survival of the Canadian film and television industry. The CRTC’s ruling that allows US streamers to own majority copyright in their new Canadian dramas turned four decades of Canadian cultural policy on its head.

The domino that might fall is whether the Liberal government would harmonize the CRTC’s new rules about the ownership of intellectual property in Canadian dramas with its own rules that govern federal subsidies to Canadian programs. The CRTC ruling invites American trade negotiators to demand it.

Online Harms

If Justice Minister Sean Fraser tables an online harms bill in Parliament, it will be time for some soul searching by all of us.

How seriously do we take the online harms of race-baiting and anti-semitic hate, humiliation of women and girls, and harm to our adolescent and teenage children? Are we virtue signalling our concern or do we really want to do something about it?

On the other hand, we shouldn’t be so naive to think that these platforms won’t err on the side of censorship rather than pay fines for permitting harmful content on their services. That’s the sort of malicious compliance Meta meted out by banning Canadian news from Facebook and Instagram rather than comply with the Online News Act.

You can see this debate play out in its beta-version with Bill S-209, tabled by an independent Senator. That bill is legislation that would require porn sites and social media apps to exclude minors from accessing hardcore porn by using third party age verification services.

Again, the harm is obviously serious, but how seriously do we take the harm? Even though the risks are remote, how much are we willing to gamble the privacy of porn site visitors and social media followers whose identities might be hacked and exposed?

All eyes will be on Australia which has grabbed global attention by banning teen access to social media, a move that requires age verification of adult social media accounts.

AI

It would be guesswork to predict what happens next with the amazing explosion of AI technology, its impact on economic growth and social harm, and government efforts to regulate it.

The most pressing policy questions are in the hands of AI Minister Evan Solomon who has frequently telegraphed his reluctance to impede the development of Canada’s fledgling AI industry by “over indexed” regulations.

But neither has Solomon warmed to the Big Tech campaign to create an American-style “text mining” exception in Canadian copyright law. If he did, he would be sinking any chances that Canadian news organizations and cultural creators have to force AI giants into paying license fees for scraping online content to feed their products. Hugh Stephens has an excellent summary of the current state of affairs, here.

The worst case scenario for content creators is very bad but grimly not a lot worse than the best case scenario.

Even if AI companies submit to paying license fees —-and there have already been a few licensing agreements struck between AI companies and a select group of big news publishers and content creators—– it’s entirely possible that in the next five years AI will so disrupt the direct interface between news organizations and news consumers that news outlets will pine for the days when Google and Meta were taking their hyperlinks for free but at least sending audience traffic their way.

Either the US or Canada may raise AI commerce or the mitigation of its harms at the CUSMA bargaining table. The Trump administration appears to be all in for making American AI into the global masters of the Internet.

But as many have pointed out there is a back eddy at state-level where MAGA politicians are as concerned about AI harms as anyone.

CBC Radio-Canada

After the CBC’s near death experience in the last federal election, policy wonks everywhere had suggestions on how the public broadcaster might re-capture the popular imagination with a strong programming line-up that resonates across the entire country.

We’ve had a statement of intent from the new CBC President: more local news, especially in the West, but what else?

If the Prime Minister gives away the media policy store to the Americans, what the CBC does becomes even more important.

Bandwidth

Whatever the government wants to do on media and cultural policy in 2026, bandwidth could be a problem.

I don’t mean download speeds. I mean the administrative bandwidth in the federal Heritage Department. Bureaucrats will be on call 24/7 during trade talks; the department is already charged with developing legislation to overhaul the governance of the CBC; and there are any number of quiet policy reviews and projects going on.

This could be the busiest year ever for media and cultural policy and the unhappy timing of Steven Guilbeault’s exit from cabinet means that we have a rookie Heritage minister, Marc Miller (who may or may not be as invested in C-11 or C-18 as Guilbeault).

Compounding that lack of experience is Carney’s decision to shuffle the deputy ministers who do the grinding work of getting things done in government. Long time Heritage deputy Isabelle Mondou just got shuffled to the Privy Council Office. Good luck to the new guy, Francis Bilodeau.

***

If you would like regular notifications of future posts from MediaPolicy.ca you can follow this site by signing up under the Follow button in the bottom right corner of the home page;

or sign up for a free subscription to MediaPolicy.ca on Substack;

or follow @howardalaw on X or Howard Law on LinkedIn.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME. But be advised they are public once I hit the “approve” button, so mark them private if you don’t want them approved.

I can be reached by e-mail at howard.law@bell.net.

This blog post is copyrighted by Howard Law, all rights reserved. 2025.